Hypophosphatemia: Main Causes and Risk Factors Explained

Hypophosphatemia Risk Factor Checker

Select your risk factors and click "Check My Risk Factors" to see detailed analysis.

Hypophosphatemia occurs when blood phosphate levels fall below 2.5 mg/dL.

Low phosphate can lead to:

- Muscle weakness

- Bone pain and fractures

- Heart rhythm abnormalities

- Fatigue and confusion

Early detection and correction are critical for preventing complications.

Chronic Kidney Disease: Impairs phosphate reabsorption in kidneys.

Alcoholism: Interferes with phosphate transporters in kidneys.

Refeeding Syndrome: Rapid calorie intake causes phosphate shift into cells.

Key Takeaways

- Hypophosphatemia happens when blood phosphate drops below 2.5mg/dL.

- Common triggers include poor dietary intake, gastrointestinal loss, renal wasting, and cellular shifts.

- Chronic kidney disease, alcoholism, and refeeding syndrome are among the biggest risk factors.

- Early detection and correction prevent muscle weakness, bone problems, and heart rhythm issues.

- Managing underlying conditions and monitoring electrolytes are essential for long‑term stability.

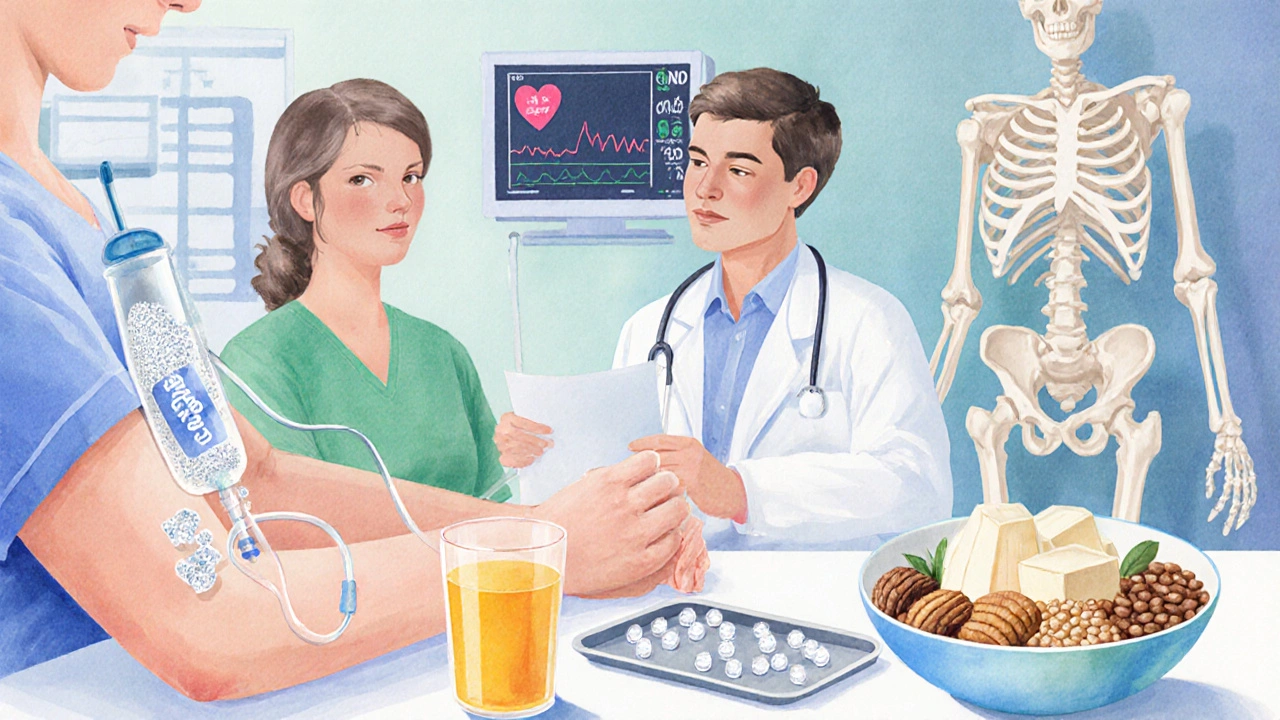

When a blood test shows a low phosphate number, doctors label the condition Hypophosphatemia as a medical disorder characterized by abnormally low serum phosphate levels. Phosphate is more than just a lab value; it fuels your cells, builds strong bones, and helps your heart beat in rhythm. If you’ve ever felt sudden muscle cramps, unexplained fatigue, or have bone pain, a dip in phosphate could be the hidden cause.

What Is Phosphate and Why It Matters?

Phosphate (Phosphate is a negatively charged mineral that combines with calcium to form bone and participates in energy transfer as part of ATP) sits at the heart of every cell’s energy cycle. Roughly 85% of the body’s phosphate resides in bone, while the remaining 15% circulates in blood and intracellular fluid. Your kidneys, gut, and hormones keep the balance tight.

The hormonal trio that regulates phosphate includes Parathyroid hormone (PTH), Vitamin D (calcitriol, the active form), and fibroblast growth factor‑23 (FGF‑23). PTH raises blood calcium but lowers phosphate by boosting renal excretion. Vitamin D does the opposite, enhancing gut absorption of both calcium and phosphate. Any disruption in this hormonal dance can tilt phosphate levels downwards.

Major Categories of Causes

Clinicians group the roots of low phosphate into four buckets: reduced intake, increased loss, redistribution into cells, and impaired production. The table below breaks each bucket down with typical examples.

| Category | Mechanism | Typical Scenarios |

|---|---|---|

| Decreased Intake | Not enough dietary phosphate | Malnutrition, prolonged fasting, low‑phosphate formulas |

| Increased Loss | Excess urinary or gastrointestinal excretion | Chronic kidney disease, Diarrhea (large fluid loss that carries phosphate), Alcoholism (impairs renal phosphate handling), certain diuretics, antacids |

| Cellular Shift | Phosphate moves from blood into cells | Refeeding syndrome, insulin therapy, respiratory alkalosis |

| Impaired Production | Reduced activation of Vitamin D or excess FGF‑23 | Tumor‑induced osteomalacia (FGF‑23 secreting tumors), Fanconi syndrome (proximal tubular defect causing phosphate wasting) |

Deep Dive into the Top Risk Factors

-

Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD)

When kidneys can’t filter effectively, they lose the ability to reabsorb phosphate. Even early‑stage CKD can cause a 10‑20% drop in serum phosphate, and the risk grows as the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) falls below 30mL/min.

-

Alcoholism

Heavy drinking interferes with the proximal tubule’s phosphate transporters. Studies from 2023 show that chronic alcoholics have a 1.8‑fold higher chance of developing hypophosphatemia after an acute binge.

-

Refeeding Syndrome

When a malnourished person suddenly receives calories, insulin spikes and drives phosphate into muscles and liver. The shift can plunge serum phosphate from normal to <2mg/dL within 24hours, especially in patients with BMI<16kg/m².

-

Diarrheal Illnesses

Gastrointestinal losses are often overlooked, but prolonged watery diarrhea can dump up to 30mmol of phosphate per day. Dehydration compounds the problem by concentrating urinary loss.

-

Medications

Loop diuretics (e.g., furosemide) increase urinary phosphate excretion. Proton‑pump inhibitors (PPIs) may reduce gut absorption of phosphate over long periods, especially in the elderly.

How Low Phosphate Shows Up Clinically

Symptoms often mimic other electrolyte issues, making diagnosis tricky. Common presentations include:

- Muscle weakness or cramps, especially after exercise.

- Fatigue and mental clouding.

- Bone pain, fractures, or slow healing.

- Cardiac arrhythmias, particularly if calcium is also low.

- Respiratory failure in severe cases due to weakened diaphragm.

Because phosphate is essential for ATP production, energy‑driven tissues like heart and skeletal muscle feel the impact first.

Laboratory Diagnosis and When to Test

A single serum phosphate measurement below 2.5mg/dL (0.81mmol/L) signals hypophosphatemia. However, ruling out a lab error is wise-repeat the test after fasting, and compare with calcium, magnesium, and alkaline phosphatase.

Additional labs help pinpoint the cause:

- Serum PTH - Elevated in renal loss, low in refeeding. \n

- 25‑OH Vitamin D - Low values point to inadequate intake or absorption.

- FGF‑23 - High levels suggest tumor‑induced osteomalacia or genetic disorders.

- Urine phosphate excretion (TmP/GFR) - Helps differentiate renal vs. gastrointestinal loss.

Management Overview

Therapy targets the root cause and replenishes phosphate safely.

-

Oral supplementation

For mild cases (<2.5mg/dL, no symptoms), oral phosphate tablets (250mg elemental phosphate) 2‑4 times daily work well. Split dosing avoids gastrointestinal upset.

-

IV replacement

Severe or symptomatic hypophosphatemia (≤1.0mg/dL) requires intravenous phosphate. Guidelines recommend 0.08mmol/kg over 6hours, with cardiac monitoring.

-

Treat underlying disorder

Adjust insulin protocols, reduce diuretic dose, treat CKD, or manage alcoholism. In refeeding syndrome, start nutrition at 10% of caloric needs and give prophylactic phosphate.

Prevention Tips for High‑Risk Groups

- Regularly screen electrolytes in CKD stages3‑5.

- Provide thiamine‑rich and phosphate‑rich meals for alcoholics in detox programs.

- When initiating total parenteral nutrition (TPN), add phosphate to the solution from day1.

- Monitor serum phosphate after major surgeries or trauma, especially if large blood losses occurred.

Quick Checklist for Clinicians

- Ask about recent weight loss, fasting, or alcohol binge.

- Review current meds - loop diuretics, antacids, insulin.

- Check renal function (eGFR) and urinary phosphate.

- Order PTH, 25‑OH Vitamin D, and FGF‑23 if cause is unclear.

- Start oral phosphate for mild cases; reserve IV for hypophosphatemia < 1mg/dL or cardiac symptoms.

Frequently Asked Questions

What serum level defines hypophosphatemia?

A serum phosphate below 2.5mg/dL (0.81mmol/L) is considered low. Levels under 1.0mg/dL are classified as severe and usually need IV therapy.

Can diet alone prevent hypophosphatemia?

A balanced diet with dairy, meat, nuts, and whole grains provides adequate phosphate. However, in kidney disease or chronic alcoholism, diet may not be enough because the body loses phosphate faster than intake can replace it.

Is hypophosphatemia dangerous for the heart?

Yes. Low phosphate can weaken cardiac muscle and predispose to arrhythmias, especially when calcium levels are also low. Prompt correction reduces the risk of life‑threatening rhythm disturbances.

How quickly can refeeding syndrome drop phosphate levels?

Within the first 24-48hours after caloric intake begins. A drop from normal to under 2mg/dL is common in severely malnourished patients if prophylactic phosphate isn’t given.

Should I stop my diuretic if I develop low phosphate?

Do not stop the medication abruptly. Discuss dosage reduction or substitution with your physician while you correct the phosphate deficit.

Are there long‑term complications if hypophosphatemia is untreated?

Chronic low phosphate can lead to osteomalacia (soft bones), repeated fractures, persistent muscle weakness, and chronic heart failure. Early treatment prevents these outcomes.

Xing yu Tao

October 5, 2025 AT 12:22In contemplating the regulatory nexus of phosphate homeostasis, one observes that the renal, gastrointestinal, and hormonal axes converge to sustain cellular energetics. The delicate balance is perturbed by chronic kidney disease, alcoholism, and refeeding syndrome, each altering phosphate reabsorption or distribution. It follows, therefore, that early identification of these risk factors is not merely clinical prudence but a philosophical imperative to preserve bodily harmony. Moreover, the interplay of PTH, vitamin D, and FGF‑23 underscores a sophisticated feedback system worthy of respect.

Adam Stewart

October 6, 2025 AT 15:12That captures the essentials succinctly.

Selena Justin

October 7, 2025 AT 18:02I appreciate the thorough overview; it really helps demystify why low phosphate can manifest as muscle cramps or bone pain. If anyone feels those symptoms, checking their recent diet, medication, and kidney function is a prudent first step. Also, staying hydrated and avoiding excessive diuretic use without medical guidance can mitigate loss.

Bernard Lingcod

October 8, 2025 AT 20:52Interesting point about the cellular shift in refeeding syndrome. The rapid insulin surge essentially drives phosphate into skeletal muscle, which explains the abrupt drop in serum levels after nutrition rehabilitation. It’s a reminder that clinicians should monitor electrolytes closely when re‑introducing calories.

Raghav Suri

October 9, 2025 AT 23:42Listen up: if you’re on loop diuretics or antacids, you’re practically inviting phosphate loss. The kidneys dump it like trash. Cut the habit or switch meds under supervision, or you’ll be battling weakness and arrhythmias. No one wants that, so act now.

Freddy Torres

October 11, 2025 AT 02:32Phosphate’s a silent powerhouse-keep it balanced, keep life vivid.

Andrew McKinnon

October 12, 2025 AT 05:23Wow, look at that-another layperson post about electrolytes. Sure, “low phosphate = bad,” but let’s not forget the underlying pathophysiology: renal tubular transporters, hormonal modulation, and osmotic gradients. If you’re not nerding out on the molecular mechanisms, you might miss the bigger clinical picture.

Dean Gill

October 13, 2025 AT 08:13When we examine hypophosphatemia through a clinical lens, several layers of complexity emerge that merit thorough discussion. First, the reduction in dietary phosphate intake, though seemingly straightforward, often reflects broader socioeconomic and nutritional patterns that can influence patient outcomes. Second, renal phosphate wasting, frequently observed in chronic kidney disease, involves alterations in the expression of sodium‑phosphate cotransporters in the proximal tubule, a process modulated by fibroblast growth factor‑23. Third, gastrointestinal losses due to chronic diarrhea or malabsorption syndromes remove phosphate directly from the lumen, compounding the deficit. Fourth, the phenomenon of cellular redistribution, as seen in refeeding syndrome, illustrates how an abrupt influx of glucose spurs insulin release, driving phosphate into skeletal muscle and hepatic cells. Fifth, hormonal dysregulation-particularly elevated parathyroid hormone-promotes phosphaturia, while insufficient active vitamin D impairs intestinal absorption. Sixth, rare entities such as tumor‑induced osteomalacia produce excess FGF‑23, leading to refractory hypophosphatemia despite supplementation. Seventh, certain medications, including loop diuretics, carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, and antacids containing aluminum or magnesium, accelerate renal phosphate loss and must be reviewed meticulously. Eighth, critical illness and sepsis can provoke respiratory alkalosis, which shifts phosphate intracellularly via pH‑dependent mechanisms. Ninth, genetic disorders like X‑linked hypophosphatemic rickets involve mutations in the PHEX gene, resulting in persistent phosphaturia. Tenth, monitoring strategies should incorporate serial serum phosphate measurements, urinary fractional excretion calculations, and, when indicated, bone densitometry to assess long‑term consequences. Eleventh, therapeutic interventions range from oral phosphate supplementation-preferably in divided doses to enhance absorption-to intravenous phosphate in severe cases with cardiac instability. Twelfth, correction must be gradual to avoid precipitating hypocalcemia or metastatic calcifications. Finally, patient education about dietary sources of phosphate, such as dairy, nuts, and legumes, alongside careful medication review, empowers individuals to mitigate risk. In sum, a multidisciplinary approach that integrates laboratory data, clinical judgement, and patient engagement is essential for effective management of hypophosphatemia.

Royberto Spencer

October 14, 2025 AT 11:03One must ask whether the very act of ignoring phosphate homeostasis reflects a broader moral failing in our approach to preventive medicine. If we allow such imbalances to fester, we betray the ethical duty to preserve the integrity of the human body.

Annette van Dijk-Leek

October 15, 2025 AT 13:53Great summary!! So many important points!!! Remember, stay hydrated!! Monitor your labs!! And don’t forget to smile!!!

Katherine M

October 16, 2025 AT 16:43Thank you for this comprehensive overview; it is both enlightening and clinically valuable 😊. The emphasis on early detection aligns with best‑practice guidelines, and the inclusion of lifestyle considerations offers a holistic perspective. I look forward to applying these insights in practice.