Obesity Pathophysiology: How Appetite and Metabolism Go Wrong

Most people think obesity is just about eating too much and moving too little. But if that were true, losing weight would be simple. The truth is far more complicated. Obesity isn’t a failure of willpower-it’s a biological malfunction. Your body’s hunger and energy-burning systems have been rewired, often without you even noticing. This isn’t about laziness. It’s about obesity pathophysiology: the broken signals inside your brain and body that make weight loss feel impossible.

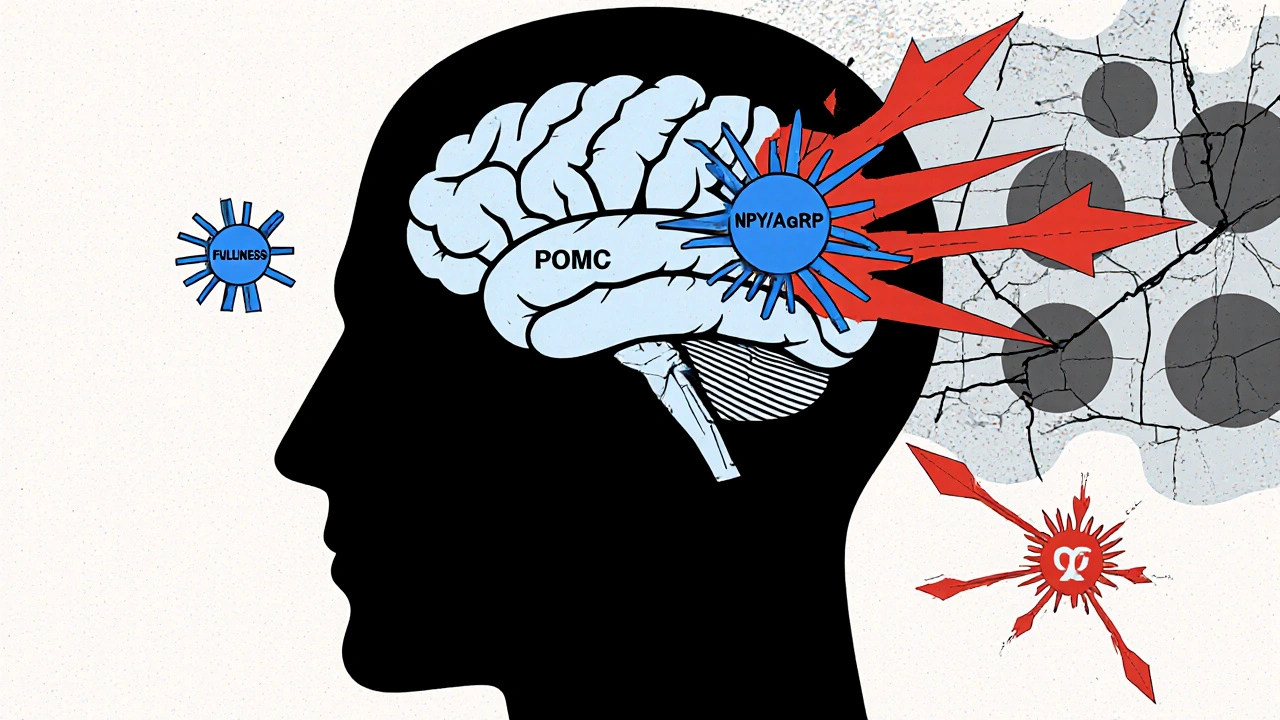

The Brain’s Hunger Switches Are Stuck

At the center of this problem is a tiny region in your brain called the arcuate nucleus. It’s like the control room for appetite. Two sets of neurons here fight for control: one tells you to stop eating, the other tells you to eat more. When they’re working right, they balance each other. In obesity, that balance collapses. The "stop eating" team is made up of POMC neurons. They release a chemical called alpha-MSH, which tells your brain you’re full. When these neurons fire, you naturally eat 25-40% less. The "eat more" team uses NPY and AgRP. Activate these neurons in a mouse, and it eats 300-500% more in minutes. In humans with obesity, this hunger signal is often too loud, and the fullness signal too quiet. What makes this worse? Fat tissue itself. As you gain weight, fat cells pump out more leptin. Leptin should tell your brain, "You’ve got enough energy stored-slow down." But in most people with obesity, the brain stops listening. This isn’t leptin deficiency-it’s leptin resistance. It’s like your car’s fuel gauge is broken. The tank is full, but the needle still says empty. So you keep driving, and keep filling up.Insulin, Ghrelin, and the Hormonal Rollercoaster

Leptin isn’t the only hormone playing a role. Insulin, which rises after meals, also tells your brain to cut back on food. But in obesity, insulin’s signal gets weaker in the brain, even as blood levels climb. Your body becomes insulin resistant everywhere-including in the appetite centers. Then there’s ghrelin, the only known hunger hormone. It spikes before meals, nudging you to eat. In lean people, ghrelin drops after eating. In many with obesity, it doesn’t drop as much. So you feel hungry again sooner. Some studies show ghrelin stays elevated even after large meals, making it harder to feel satisfied. And it’s not just about hunger. Your body’s energy-burning systems are also slowing down. Brown fat, which burns calories to make heat, becomes less active. Muscle tissue becomes less efficient at using energy. Even resting metabolism drops. You’re not just eating more-you’re burning less, even when you’re not moving.The Broken Wiring Behind the Scenes

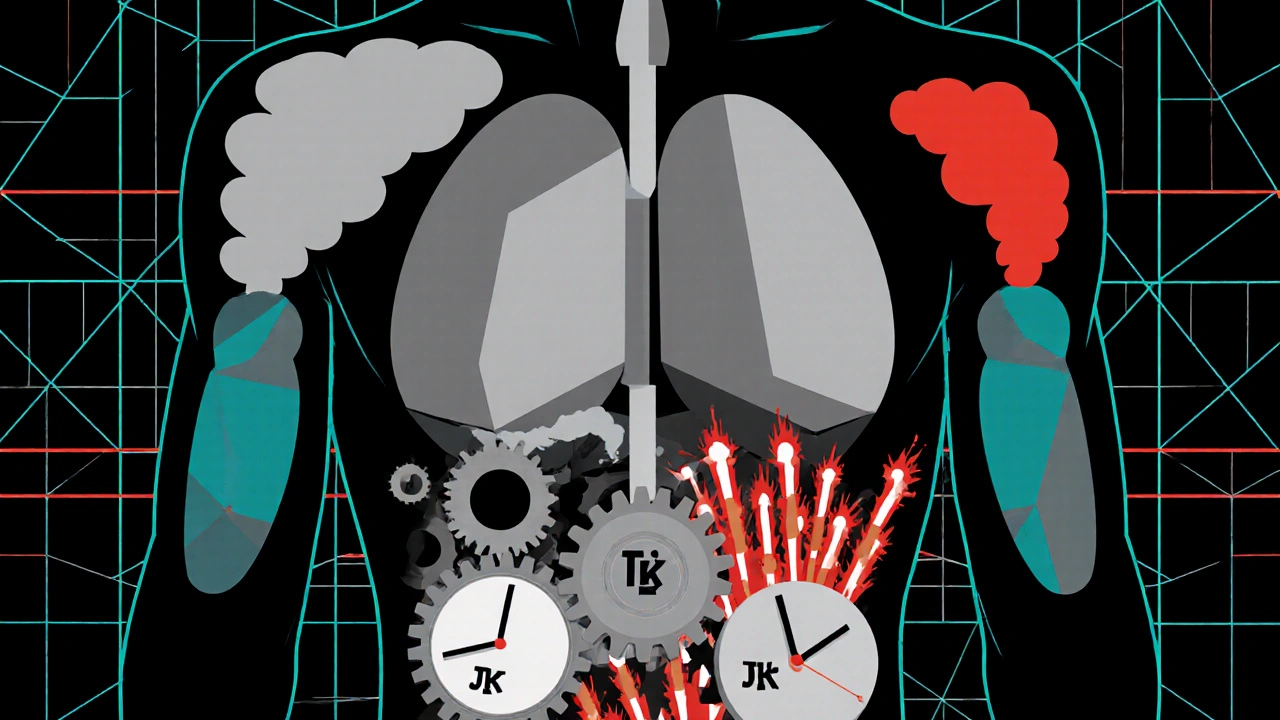

Inside brain cells, signaling pathways that should respond to leptin and insulin are clogged. The PI3K-AKT pathway is one of the main lines of communication. When leptin binds to its receptor, it should trigger this pathway to reduce hunger. But in obesity, this line gets jammed. Studies show that blocking PI3K in the brain makes leptin completely ineffective. That’s why weight loss drugs that target this pathway-like setmelanotide-work only in rare cases where the genetic wiring is broken from birth. Another key player is mTOR, a cellular sensor that responds to nutrients. When you eat, mTOR tells your brain you’ve got fuel. Stimulating mTOR reduces food intake by 25% in mice. But in obesity, this system gets confused. Constant overeating floods the system, and it starts ignoring the signals. Even the body’s inflammatory response plays a part. Fat tissue in obesity releases chemicals that activate JNK, a stress pathway that blocks leptin signaling. It’s a vicious cycle: more fat → more inflammation → more leptin resistance → more eating → more fat.

Why Diets Fail (It’s Not Your Fault)

When you lose weight, your body doesn’t think you’re winning. It thinks you’re starving. Leptin levels crash. Ghrelin spikes. Your metabolism slows. Your brain craves high-calorie foods more intensely. This isn’t weakness. It’s biology. A 2021 study tracking people after weight loss found that their leptin levels stayed low for a full year-even after they regained none of the weight. Their bodies were still in starvation mode. That’s why most people regain weight. The system is designed to defend a higher weight, not a lower one. This is why simple advice like "eat less, move more" fails. It ignores the biological forces working against you. You’re not fighting your willpower-you’re fighting your own physiology.Who’s Most at Risk? The Hidden Triggers

Not everyone with obesity has the same biology. Some have genetic mutations. Fewer than 50 people worldwide have leptin deficiency. But millions have what’s called "common obesity"-where the system breaks down over time due to environment, age, or hormones. Post-menopausal women are a prime example. Estrogen helps regulate fat distribution and appetite. When estrogen drops after menopause, women gain belly fat faster. Studies in mice show that removing estrogen receptors leads to 25% more food intake and 30% less energy use. That’s why weight gain after 50 isn’t just about slowing metabolism-it’s hormonal. People with Prader-Willi syndrome have extremely low levels of pancreatic polypeptide (PP), a hormone that tells your stomach to slow down after eating. Without PP, they never feel full. That’s why they’re constantly hungry. Even in common obesity, 60% of people have lower-than-normal PP levels. And then there’s sleep. People with narcolepsy have a 2-3 times higher risk of obesity. Why? Their orexin system, which links wakefulness to appetite, is broken. Orexin normally keeps you alert and active. When it’s low, you’re tired, crave carbs, and move less.

swatantra kumar

November 21, 2025 AT 01:33robert cardy solano

November 23, 2025 AT 00:04Pawan Jamwal

November 24, 2025 AT 00:53Bill Camp

November 25, 2025 AT 07:18Sarah Swiatek

November 27, 2025 AT 01:01Cinkoon Marketing

November 28, 2025 AT 18:13Lemmy Coco

November 29, 2025 AT 14:36rob lafata

December 1, 2025 AT 13:02Matthew McCraney

December 3, 2025 AT 10:33serge jane

December 3, 2025 AT 17:52Nick Naylor

December 4, 2025 AT 17:56