Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DRESS): What You Need to Know

DRESS Syndrome Diagnostic Tool

DRESS Syndrome Diagnostic Assessment

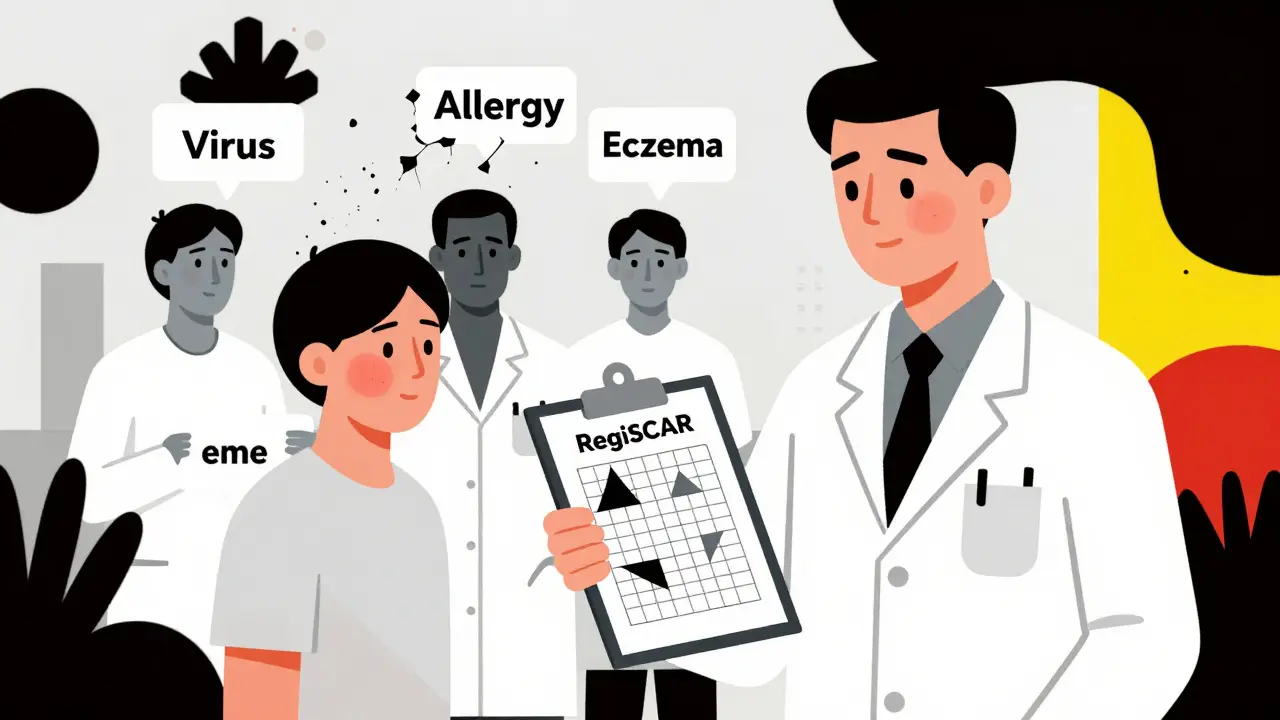

A clinical tool based on the RegiSCAR scoring system to help identify Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DRESS) syndrome

Please answer these questions:

Based on the article content, DRESS syndrome is identified using the RegiSCAR scoring system. Answer the following questions to assess the likelihood of DRESS.

Diagnosis Result

DRESS syndrome is not just a rash. It’s a full-body emergency that can turn a routine medication into a life-threatening event. If you’ve taken an anticonvulsant, allopurinol, or certain antibiotics and developed a fever, swollen glands, and a spreading red rash three weeks later, this isn’t a virus or an allergy-it could be DRESS. And if it’s missed, the chance of dying rises sharply. This isn’t rare. It happens in about 1 out of every 1,000 people taking high-risk drugs. Yet most doctors never see it. That’s why so many patients go from ER to ER before getting the right answer.

What DRESS Actually Looks Like

DRESS doesn’t start with a sudden blister or peeling skin like Stevens-Johnson Syndrome. It creeps in. You start feeling unwell-low-grade fever, fatigue-maybe a week or two after starting a new pill. Then the rash appears. Not small spots, but hundreds of flat, red, slightly raised bumps that spread from your face and chest down to your arms and legs. Your face swells. Your lips crack and dry out. Your lymph nodes in the neck or armpits become hard and tender. This isn’t a coincidence. It’s the body’s immune system going haywire.

By the time you’re at the doctor’s office, your liver enzymes are sky-high. ALT levels above 300 IU/L are common. Eosinophils, a type of white blood cell usually under 500 per microliter, are now over 1,500-sometimes hitting 5,000. That’s the hallmark. You don’t just have a rash. You have a systemic meltdown. About 90% of patients show organ damage. The liver takes the hardest hit, with 78% developing hepatitis. Kidneys, lungs, heart, and pancreas can follow. In 10% of cases, it kills.

Why It Happens: More Than Just the Drug

It’s not just the medication. It’s the combination. DRESS only happens in people with certain genetic markers. If you carry HLA-B*58:01, taking allopurinol for gout puts you at extreme risk. If you have HLA-A*31:01, carbamazepine for seizures can trigger it. These genes aren’t rare-they’re common in certain populations. In Taiwan, doctors screen everyone before prescribing allopurinol. Since 2012, DRESS cases from that drug have dropped by 80%.

But here’s the twist: the drug alone isn’t enough. In 60 to 80% of cases, a dormant virus wakes up. HHV-6, the same virus that causes roseola in babies, reactivates in the bloodstream. That’s when the immune system goes into overdrive. The drug triggers the reaction, but the virus fuels it. That’s why antivirals sometimes help, even though they’re not standard treatment. This isn’t a simple allergy. It’s an autoimmune storm triggered by a drug and a virus.

How Doctors Miss It-And How to Spot It

Most patients see three or more doctors before DRESS is diagnosed. Why? Because it looks like everything else. A viral infection. A bacterial illness. A drug allergy. Even eczema. In one study, 42% of early DRESS cases were labeled as viral illnesses. Primary care doctors rarely see it-only 38% can correctly identify the diagnostic criteria. Dermatologists? 89% can.

Here’s how to cut through the confusion. Ask these three questions:

- Did the patient start a new medication 2 to 8 weeks ago?

- Is there a fever over 38.5°C (101.3°F) plus a widespread rash?

- Are eosinophils above 1,500 and liver enzymes elevated?

If the answer is yes to all three, DRESS is likely. Use the RegiSCAR scoring system-it’s the gold standard. It gives you a point for each feature: rash, fever, organ involvement, eosinophilia, lymphadenopathy, and viral reactivation. A score of 4 or higher is definite. A score of 2 or 3 is probable. Anything below 2? Probably not DRESS.

Don’t wait for a skin biopsy. Don’t rely on a negative allergy test. The diagnosis is clinical. If you suspect it, stop the drug immediately. No exceptions. Even if the patient says, “But I need this for my pain.” That pill is now a weapon.

What Happens After Diagnosis

Once DRESS is confirmed, the first step is stopping the drug. The second is hospitalization. Most patients need ICU-level monitoring if liver enzymes are above 1,000, creatinine is over 2.0, or breathing is affected. Steroids are the main treatment. Prednisone, started within 72 hours, works in 60 to 70% of cases. But it’s not a quick fix. Tapering takes 3 to 6 months. Go too fast, and the reaction comes back harder.

Some patients need more. IVIG (intravenous immunoglobulin) is used in severe cases. Mycophenolate is being tested in clinical trials as a steroid-sparing option. In rare cases, plasmapheresis or cyclosporine is tried. But there are no large randomized trials. Most of what we know comes from case series and expert opinion. That’s the uncomfortable truth: we’re treating a deadly disease with evidence that’s mostly observational.

Recovery isn’t guaranteed. About 20% of survivors develop long-term problems: chronic kidney disease, autoimmune thyroiditis, or type 1 diabetes. One patient in a 2022 study developed permanent kidney failure after 22 days of misdiagnosis. Another recovered fully after 8 weeks in the hospital and 6 months of tapering steroids-then went back to work as a nurse.

The Hidden Crisis: Access and Awareness

DRESS doesn’t care about your income or zip code. But your chances of surviving it do. Academic hospitals have protocols. Community clinics? Often not. A 2021 study found community hospitals are 3.7 times less likely to have DRESS management guidelines than teaching hospitals. That means a patient in rural Ohio might wait days longer than one in Boston.

And cost? A single DRESS hospitalization averages $28,500 in the U.S. That’s not counting lost wages, follow-up care, or chronic complications. Yet the FDA only mandates HLA screening for allopurinol in patients of Asian descent. In Taiwan, it’s universal. In the U.S., it’s optional. The FDA approved a point-of-care HLA-B*58:01 test in March 2023-it gives results in under an hour. But most pharmacies don’t stock it. Most doctors don’t know it exists.

Patients are pushing for change. The DRESS Syndrome Foundation, with over 1,200 members, has become a lifeline. Ninety-two percent of surveyed patients say the Foundation’s rapid consultation service saved them. Their global registry, launched in September 2023, now includes 47 sites across 15 countries. That’s how science moves forward-not just in labs, but in patient stories.

What You Should Do Now

If you’re on allopurinol, carbamazepine, phenytoin, lamotrigine, vancomycin, or sulfonamide antibiotics, know the signs. Fever, rash, swollen glands-after three weeks? Don’t brush it off. Go to the ER. Say, “I think I might have DRESS syndrome.” Bring a list of your medications. Ask for a CBC with differential and liver enzymes.

If you’re a doctor: screen for HLA-B*58:01 before prescribing allopurinol. Especially in patients of Asian descent. Use RegiSCAR. Don’t wait for a biopsy. Stop the drug immediately. Call a dermatologist. Don’t assume it’s “just an allergy.”

DRESS is preventable. It’s treatable. But only if you recognize it in time. The tools are here. The knowledge is out there. What’s missing is urgency.

ellen adamina

January 14, 2026 AT 13:31Gloria Montero Puertas

January 15, 2026 AT 16:52Tom Doan

January 16, 2026 AT 20:17Dan Mack

January 17, 2026 AT 21:23Amy Vickberg

January 17, 2026 AT 23:12Nicholas Urmaza

January 19, 2026 AT 09:26Sarah Mailloux

January 19, 2026 AT 10:54Nilesh Khedekar

January 20, 2026 AT 21:46