FDA Generic Drug Approval: Complete Step-by-Step Process

How the FDA Approves Generic Drugs: A Clear Step-by-Step Guide

If you’ve ever picked up a prescription and seen a generic version on the shelf, you’re seeing the result of one of the most efficient regulatory systems in the world. The FDA doesn’t just approve any drug that looks like the brand-name version. There’s a strict, science-backed process behind every generic pill, patch, or injection you take. And it’s not magic-it’s called the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA). This system, created by the Hatch-Waxman Act in 1984, lets generic manufacturers bring affordable medicines to market without repeating every single clinical trial. But that doesn’t mean it’s easy. Far from it.

Every year, the FDA approves over 1,000 generic drugs. In 2023 alone, they approved 1,087. That’s not random luck. It’s the outcome of a highly structured, multi-year process that demands precision, documentation, and compliance at every stage. If you’re a manufacturer, a pharmacist, or just someone curious about how your $4 blood pressure pill got to the pharmacy, here’s exactly how it works.

Step 1: Identify the Reference Listed Drug (RLD)

Before a generic company can even start, they need to pick the right brand-name drug to copy. That’s called the Reference Listed Drug, or RLD. It’s not just any similar drug-it has to be the exact one the FDA has already approved and listed in the Orange Book, the official directory of approved drug products with therapeutic equivalence ratings.

For example, if you want to make a generic version of Lipitor (atorvastatin), you must use the FDA-approved Lipitor as your RLD. You can’t pick a different brand or a foreign version. The RLD sets the standard for everything: strength, dosage form, route of administration, and even the inactive ingredients must be safe and comparable. The FDA checks this carefully because if the RLD is wrong, the whole application fails.

Step 2: Prove Pharmaceutical Equivalence

Pharmaceutical equivalence means your generic has the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration as the RLD. No exceptions. If the brand is a 20 mg tablet taken by mouth, your generic must be identical in those four areas.

But here’s where people get confused: the inactive ingredients don’t have to match. Your generic can use different fillers, dyes, or coatings-as long as they’re safe and don’t change how the drug works. The FDA allows this because some people have allergies to certain dyes or preservatives, and generics can offer alternatives without compromising effectiveness.

Manufacturers must submit detailed chemistry, manufacturing, and controls (CMC) data showing their production process is consistent, repeatable, and meets Current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMP). This includes everything from the purity of the active ingredient to how the tablets are pressed and packaged. The FDA inspects these manufacturing sites-often without warning-to make sure they’re not cutting corners.

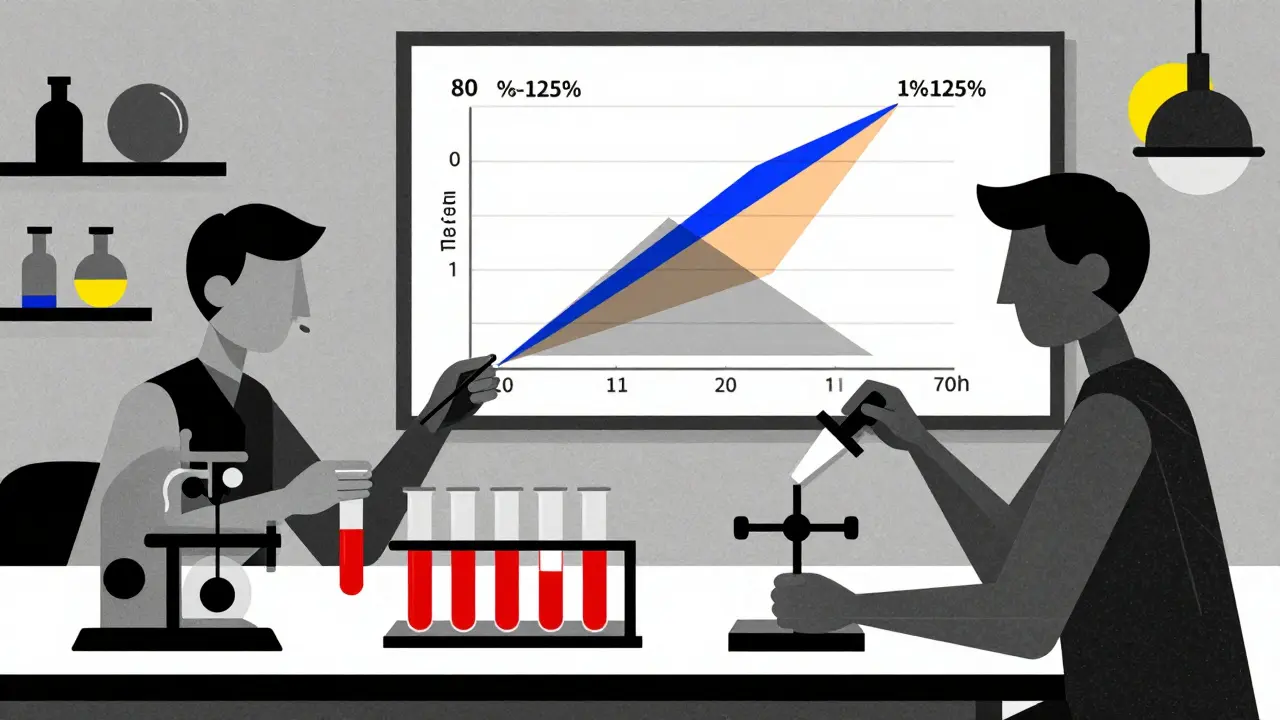

Step 3: Demonstrate Bioequivalence

This is the most critical step. A generic drug must deliver the same amount of active ingredient into the bloodstream at the same rate as the brand-name drug. That’s called bioequivalence. The FDA defines it as: the 90% confidence interval for the ratio of the generic to the brand must fall between 80% and 125% for both the maximum concentration (Cmax) and total exposure (AUC).

How do they test this? In a small clinical study with 24 to 36 healthy volunteers. These people take the brand-name drug on one day, then the generic on another, with a washout period in between. Blood samples are taken at frequent intervals to measure how much of the drug enters their system and how fast.

This isn’t a test of whether the drug works for high blood pressure or diabetes-it’s a test of whether your body absorbs it the same way. If the numbers fall outside that 80-125% range, the FDA will reject the application. That’s why some generics fail even when they look identical on the bottle. A 2023 FDA report found that 28% of ANDA deficiencies were due to flawed bioequivalence studies.

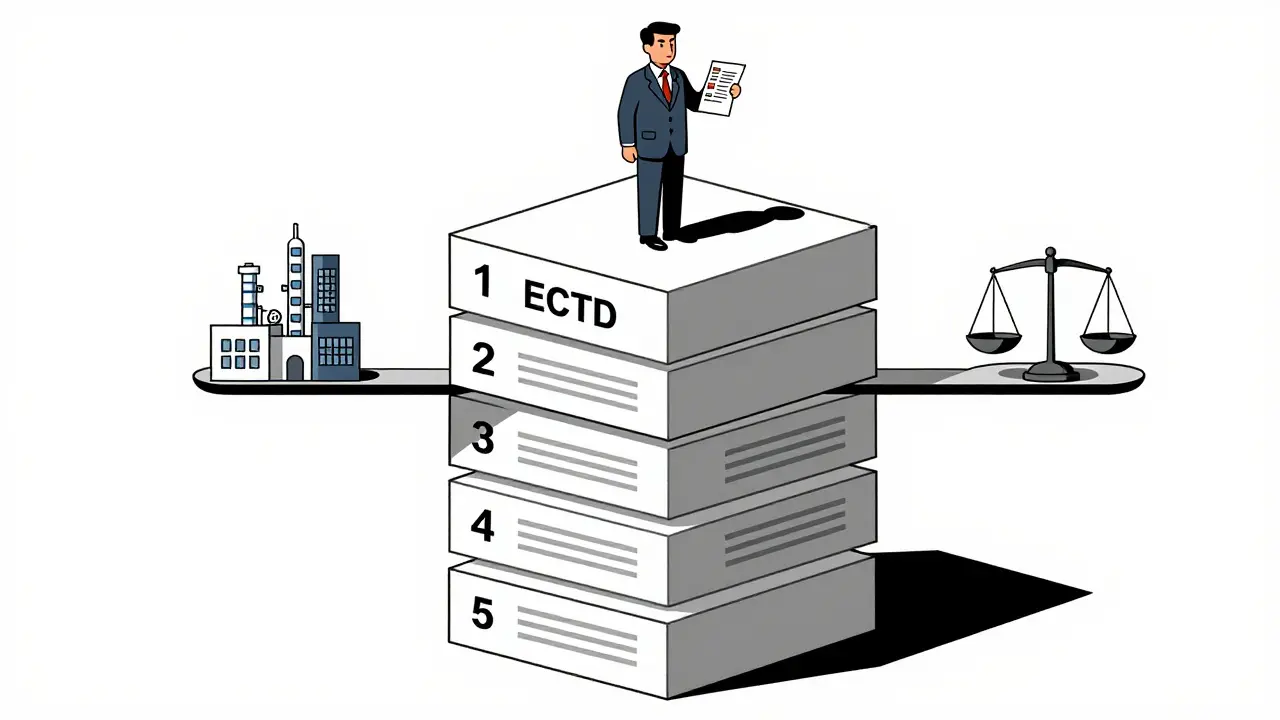

Step 4: Prepare and Submit the ANDA

The ANDA isn’t a one-page form. It’s a massive dossier-usually hundreds of pages-organized in the electronic Common Technical Document (eCTD) format. This is the global standard for drug submissions. The ANDA includes five modules:

- Module 1: Administrative information (company details, application type, fees)

- Module 2: Summaries of quality, nonclinical, and clinical data

- Module 3: Detailed chemistry, manufacturing, and controls (CMC)

- Module 4: Nonclinical study reports (toxicology, pharmacology)

- Module 5: Clinical study reports (bioequivalence data)

Everything must be formatted exactly right. If a single file is misnamed or a table isn’t labeled properly, the FDA can refuse to file it. That’s not a rejection-it’s a delay. The FDA has 60 days to review the submission for completeness. If it’s incomplete, you get a Refuse to File letter and have to start over.

Step 5: FDA Review and Inspection

Once the ANDA is accepted, the clock starts. Under the Generic Drug User Fee Amendments (GDUFA), the FDA aims to review 90% of original ANDAs within 10 months. That’s the standard. But the clock doesn’t tick continuously. If the FDA has questions, they send an Information Request (IR). The manufacturer has to respond within 10 days. If they don’t, the review pauses.

Most ANDAs get reviewed by a team of scientists-pharmacists, chemists, statisticians, and engineers. They check every detail: the dissolution profile of the tablets, the stability of the formulation over time, the sterility of injectables. They also inspect the manufacturing facility. About 22% of rejections come from inspection issues-dirty equipment, poor documentation, or unapproved changes in the production line.

Only about 75% of ANDAs get approved on the first try. The rest get a Complete Response Letter (CRL), which lists every deficiency. Some companies get one CRL. Others get three or more. One Reddit user reported a nasal spray ANDA that took 28 months and $2.3 million in extra testing because the FDA questioned the bioequivalence method.

Step 6: Patent and Exclusivity Considerations

Generic manufacturers can’t just jump in the moment a brand drug hits the market. Patents protect the original drug for up to 20 years from filing. But there’s a legal loophole: the Paragraph IV certification.

If a generic company believes a patent is invalid or won’t be infringed, they can file a Paragraph IV certification with their ANDA. This triggers a 45-day window for the brand-name company to sue. If they do, the FDA can’t approve the generic for 30 months-or until a court rules in the generic company’s favor.

This is where the real financial stakes kick in. The first generic company to successfully challenge a patent gets 180 days of market exclusivity. During that time, no other generic can enter. That’s why companies like Teva and Mylan spend millions on legal teams. In 2023, the first generic version of Humira generated over $1.2 billion in sales during its exclusivity period.

Step 7: Approval and Market Entry

When the FDA finally says yes, the generic drug is added to the Orange Book with an “AB” rating-meaning it’s therapeutically equivalent to the brand. Pharmacies can now substitute it automatically. The manufacturer can start shipping.

But approval doesn’t mean the work is over. The FDA still monitors the drug after it hits the market. If there are reports of side effects, inconsistent performance, or manufacturing problems, the FDA can pull it. In 2022, they recalled several generic metformin products due to NDMA contamination. That’s why ongoing quality control is part of the deal.

Why This Process Matters

Generic drugs make up 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. But they cost only 23% of what brand-name drugs do. That’s not a coincidence. It’s the direct result of the ANDA system. In 2023, generics saved the U.S. healthcare system $373 billion. That’s money that goes back into hospitals, insurance, and patients’ pockets.

But it’s not perfect. Complex drugs-like inhalers, injectables, or topical creams-are harder to copy. The FDA has launched the Complex Generic Drug Products Initiative to improve how these are reviewed. And while most generics are safe and effective, there have been rare cases where manufacturing differences affected outcomes, especially with drugs that have a narrow therapeutic index-like warfarin or lithium.

Still, the system works. The FDA’s goal under GDUFA IV is to cut the median review time to 8 months and reduce the backlog to under 300 applications by 2025. They’re also testing AI tools to sort through documents faster. The future of generic approval isn’t just about speed-it’s about smarter, more consistent reviews.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

If you’re trying to navigate this process, here are the biggest mistakes companies make-and how to dodge them:

- Skipping pre-submission meetings: The FDA offers these for free. Use them. Ask questions before you spend millions.

- Underestimating CMC: Chemistry and manufacturing data is the #1 reason for rejection. Don’t rush it.

- Ignoring bioequivalence design: Work with a bioanalytical lab that’s done this before. Don’t try to cut costs here.

- Waiting until the last minute: ANDA prep takes 11-19 months. Start early.

- Not preparing for inspections: Your facility must be inspection-ready from day one. Train your team like it’s a surprise audit.

The most successful applicants don’t just follow the rules-they anticipate them. They build teams with regulatory affairs specialists, formulation scientists, and QA experts working together from day one. They don’t treat the ANDA as a paperwork exercise. They treat it like a scientific challenge.

Frequently Asked Questions

How long does it take to get a generic drug approved by the FDA?

The FDA aims to review a complete ANDA within 10 months. But the entire process-from starting development to approval-typically takes 3 to 4 years. This includes 6-9 months for bioequivalence studies, 3-6 months for manufacturing development, and 2-4 months to prepare the application. Delays happen if the FDA issues a Complete Response Letter or if patent litigation occurs.

Are generic drugs as safe and effective as brand-name drugs?

Yes. The FDA requires generics to meet the same strict standards for quality, strength, purity, and stability as brand-name drugs. Bioequivalence studies prove they work the same way in the body. Over 90% of prescriptions in the U.S. are filled with generics, and decades of real-world use confirm they’re just as safe and effective.

What’s the difference between an ANDA and an NDA?

An NDA (New Drug Application) is for brand-name drugs and requires full clinical trials to prove safety and effectiveness. An ANDA (Abbreviated New Drug Application) is for generics and relies on the brand’s existing data. The ANDA only needs to prove pharmaceutical and bioequivalence, which cuts development time from 10-15 years to 3-4 years and reduces costs from billions to millions.

Can a generic drug be approved before the brand-name patent expires?

Yes, but only if the generic company files a Paragraph IV certification challenging the patent’s validity or claiming it won’t be infringed. This triggers a legal process. The FDA cannot approve the generic until 30 months after the patent holder files suit, unless a court rules in favor of the generic manufacturer first.

Why do some generic drugs have different colors or shapes than the brand?

The active ingredient must be identical, but inactive ingredients-like dyes, fillers, or coatings-can differ. These changes don’t affect how the drug works. Companies often change the appearance to avoid trademark infringement or to make pills easier to swallow. The FDA ensures these changes are safe and don’t alter absorption.

What Comes Next?

The generic drug system isn’t static. With biosimilars gaining traction and AI tools being tested for document review, the future is moving faster. The FDA’s goal is clear: get safe, affordable medicines to patients as quickly as possible-without sacrificing quality.

For manufacturers, the path is tough but worth it. For patients, it’s the reason they can afford their meds. And for the healthcare system, it’s the backbone of cost control. The ANDA process isn’t perfect-but it’s the best system we have. And it’s working.