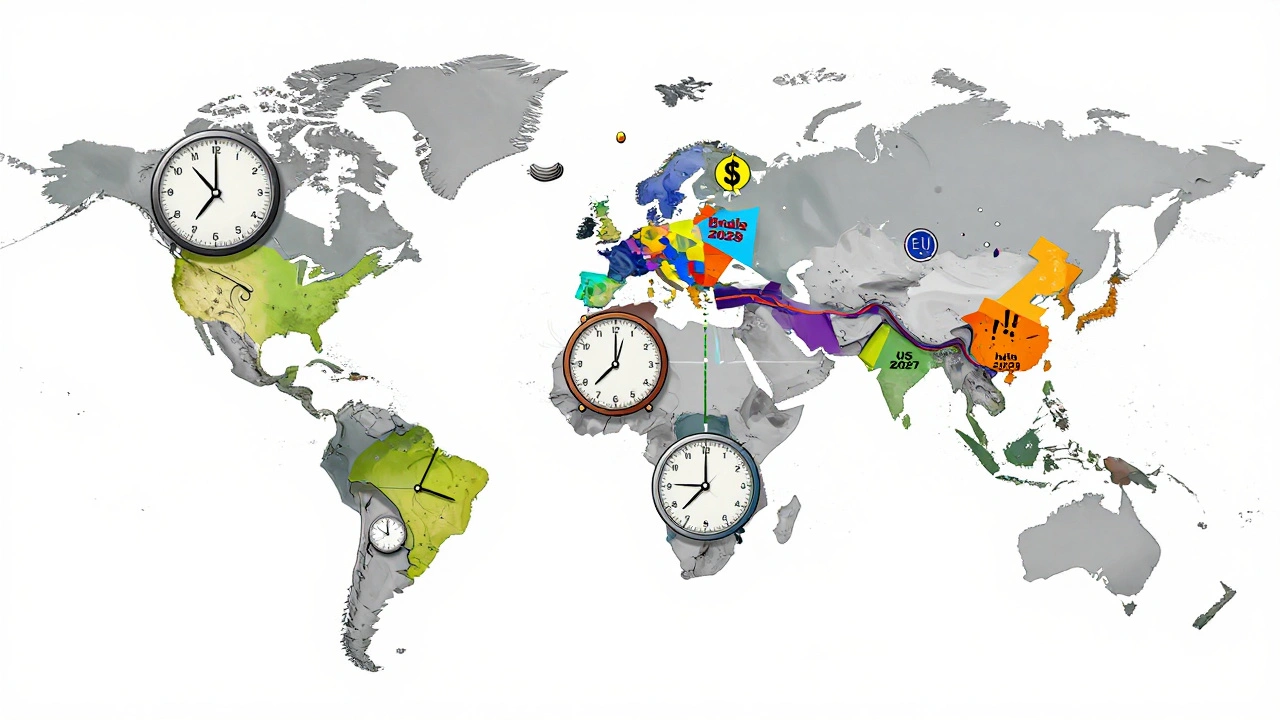

International Patent Expiration: How Timelines Vary Around the World

Most people think a patent lasts 20 years-simple, right? But if you’ve ever tried to track when a patent actually expires across different countries, you know it’s anything but simple. A drug patent filed in the U.S. might expire in 2030, but the same invention could be protected in Brazil until 2035-or expire in 2028 if maintenance fees weren’t paid. Why? Because international patent expiration isn’t governed by one global clock. It’s a patchwork of laws, delays, fees, and exceptions that change from country to country.

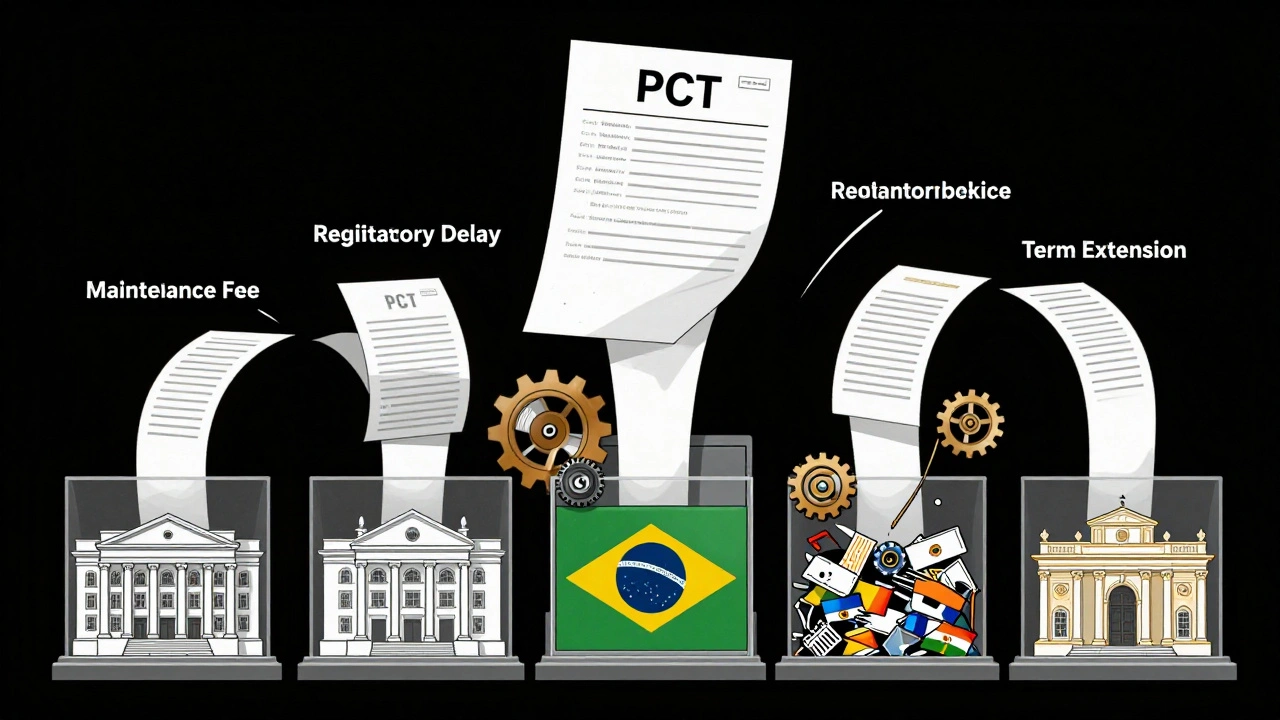

There’s no such thing as a global patent

You can’t file one patent and have it work everywhere. That’s a common myth. What exists instead is the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT), which lets you file one application that starts the process in over 150 countries. But this isn’t a global patent. It’s a delay tactic. After filing, you get 30 or 31 months (depending on the country) to decide where you actually want protection. Only then do you enter the national phase-submitting separate applications to each country’s patent office. Each one then applies its own rules.That means your patent’s expiration date isn’t set on the day you file. It’s set by the earliest filing date you claim, usually from your first application. But even that date can be tricky. Provisional applications in the U.S. don’t count toward the 20-year term-they just lock in your priority date. So if you file a provisional in January 2023, then a non-provisional in December 2023, your 20-year clock starts in January 2023. But if you skip the provisional and file directly in 2023, the clock starts in December 2023. That’s a whole year’s difference.

The 20-year rule isn’t always the full story

The World Trade Organization’s TRIPS Agreement, which came into effect in 1995, set the global baseline: patents must last at least 20 years from the filing date. Almost every major economy follows this. The U.S., Japan, Germany, China, Canada, Australia-they all use 20 years from filing as the starting point.But here’s where it gets messy. Before 1995, the U.S. gave patents 17 years from the issue date. So if a patent was filed in 1990 but granted in 1997, it expired in 2014-not 2010. Even today, some older patents still follow that old rule. And if a patent was filed just before June 8, 1995, it gets the longer of the two terms: 20 years from filing or 17 years from grant. That means some U.S. patents are still alive today because they were granted late under the old system.

Canada still has a similar hybrid system for patents filed before October 1, 1989. Those expire at the later of 20 years from filing or 17 years from grant. That’s not a glitch-it’s legacy law. And in Brazil, even though the law says 20 years, the patent office backlog is so bad that many patents only get examined 10 or 12 years after filing. That means the effective term-the time the patent is actually enforceable-is often less than 10 years. Companies in Brazil know this. They plan their product launches around when the patent will be granted, not when it was filed.

Patent term extensions: when the clock gets reset

If your patent is for a drug, medical device, or pesticide, the 20-year clock might not be the end of the story. Regulatory approval can take years. The FDA in the U.S. might take 8 years to approve a new drug. That eats up half your patent life before you even sell anything.To fix that, many countries allow patent term extensions. The U.S. has the Patent Term Extension (PTE) under 35 U.S.C. § 156. It can add up to 5 years, plus a possible 6-month pediatric extension. The European Union does something similar with Supplementary Protection Certificates (SPCs). These can extend protection by up to 5 years, and another 6 months if you test the drug on children. Japan and China also have patent term compensation systems for unreasonable delays in examination or regulatory approval.

But not every country plays fair. India doesn’t offer any extensions, no matter how long the approval process takes. Australia has limited extensions for office delays, but only if the delay exceeds a certain threshold. And in countries like South Korea and Mexico, extensions are either rare or non-existent. That’s why pharmaceutical companies file patents in the U.S. and EU first-they know they can get more time there.

Maintenance fees: the silent killer of patents

Even if your patent is technically still alive, it can die quietly. Most countries require you to pay maintenance fees-sometimes called annuities-to keep the patent active. Miss a payment, and your patent expires, even if you’re only 5 years into the 20-year term.In the U.S., you pay at 3.5, 7.5, and 11.5 years after grant. There’s a 6-month grace period, but you pay extra. In Europe, fees are paid annually starting from the third year. In Japan, you pay at years 3, 7, and 10. In Mexico, you pay four times-at 5, 10, 15, and 20 years. And in Switzerland? You pay just once, at grant. That’s it.

Small businesses and individual inventors often run into trouble here. They get excited about their patent, pay the initial fees, and then forget about the ongoing costs. A 2022 study by the European Patent Office found that nearly 18% of patents in Europe expire because the owner didn’t pay the maintenance fee. That’s not a legal technicality-it’s a business mistake. And once it’s gone, you can’t get it back.

Utility models: the short-term alternative

Not every invention needs 20 years. In countries like Germany, China, Japan, and Australia, you can file for a utility model instead of a full patent. These are simpler, faster, and cheaper. But they come with a trade-off: protection lasts only 6 to 10 years.Utility models are great for mechanical devices, tools, or consumer products with a short market life. They don’t require the same level of inventive step as a patent, so they’re easier to get. In China, over 40% of all patent-like protections are utility models. In Germany, they’re called “Gebrauchsmuster” and account for nearly 30% of all filings. But here’s the catch: you can’t extend them. No regulatory delays, no extensions. Once the 10 years are up, it’s over.

The EU’s new Unitary Patent changes the game

In June 2023, the European Union launched its Unitary Patent system. Before this, if you wanted a patent in 10 EU countries, you had to pay separate validation fees in each one, hire local attorneys, and track 10 different maintenance schedules. Now, you can get a single patent with effect in 17 participating countries-all under one renewal fee, one expiration date.But here’s the twist: the expiration is still 20 years from the filing date. The Unitary Patent doesn’t change the term. It just simplifies the process. So if you filed in 2020, your patent expires in 2040, whether you chose the old system or the new one. The benefit isn’t longer protection-it’s less paperwork.

What this means for global businesses

If you’re a company selling products in multiple countries, you need to treat patent expiration like a calendar you’re managing across 50 time zones. A drug patent might expire in the U.S. in 2027, but in Brazil, it won’t expire until 2031 because of delays in examination. In India, it might expire in 2026 because no extensions are allowed. Your generic competitor in India can launch in 2026. Your competitor in Brazil has to wait until 2031.That’s why big pharma companies like Pfizer and Johnson & Johnson have teams dedicated to tracking patent expirations. They don’t just look at the filing date. They track:

- Priority date

- Patent office delays

- Regulatory approval timelines

- Maintenance fee deadlines

- Country-specific extensions

They use software that pulls data from patent offices, calculates expiration dates automatically, and flags when fees are due. Without that, you’re flying blind.

What about emerging markets?

Countries like Indonesia and Vietnam used to have shorter patent terms-15 years. But they changed their laws in 2016 and 2022 respectively to match the 20-year global standard. Why? Because they want foreign investment. Companies won’t spend billions on R&D if they can’t protect it for long enough.But enforcement is still a problem. In some countries, even if a patent is valid, courts are slow or biased. A patent might be technically valid for 20 years, but if you can’t enforce it, the real term is zero. That’s why companies often rely on trade secrets or first-mover advantage in markets with weak IP enforcement.

How to manage patent expiration in practice

If you’re managing a global patent portfolio, here’s what you need to do:- Track the priority date-not the filing date in each country.

- Know the national phase deadlines: 30 months in the U.S., 31 in most of Europe and Asia.

- Calculate patent term adjustments: Did the patent office delay your examination? You might get extra time.

- Set alerts for maintenance fees: Use a system, not a spreadsheet.

- Check for extensions: Are you in the U.S., EU, Japan, or China? You might get more time.

- Consider utility models for fast-moving products.

- Don’t assume expiration is the same everywhere.

One mistake-missing a fee in Germany or forgetting to request a PTE in the U.S.-can cost you millions in lost revenue. Patents aren’t just legal documents. They’re financial assets. And like any asset, they need active management.

Do all countries have a 20-year patent term?

Most do, but not all. Nearly all WTO member countries follow the 20-year standard from filing date, thanks to the TRIPS Agreement. However, some countries still have legacy patents that follow older rules, like the U.S. and Canada, where some patents expire 17 years from grant. Also, utility models in countries like Germany and China last only 6 to 10 years. And in places like Brazil, long delays mean the effective term is often much shorter than 20 years.

Can a patent expire before 20 years?

Yes. The most common reason is failure to pay maintenance fees. If you miss a payment in the U.S., Europe, Japan, or anywhere else that requires them, your patent dies-even if you’re only 10 years in. Patents can also expire early if the owner voluntarily abandons them or if a court invalidates them. And in countries with slow patent offices, like Brazil or India, a patent might not be granted until 12 years after filing, leaving only 8 years of enforceable life.

How do patent term extensions work for drugs?

In the U.S., the Patent Term Extension (PTE) can add up to 5 years to compensate for FDA review delays, plus a possible 6-month extension for pediatric testing. The EU offers Supplementary Protection Certificates (SPCs) with similar rules. Japan and China also allow extensions for unreasonable examination or regulatory delays. But countries like India, Australia (for regulatory delays), and most developing nations offer no such extensions. This is why drug companies focus their commercialization efforts on markets that offer longer protection.

What’s the difference between a PCT application and a global patent?

A PCT application is not a patent. It’s a way to delay filing in individual countries for up to 30 or 31 months. After that, you must enter the national phase in each country where you want protection. Each country then examines and grants its own patent. There is no such thing as a single international patent that covers all countries. The PCT only streamlines the process-it doesn’t create global rights.

Why does the U.S. have such complicated patent expiration rules?

The U.S. changed its patent system in 1995 to align with international standards, but kept rules for older patents. This created a hybrid system where some patents expire 20 years from filing, others 17 years from grant, and some get both. Add in patent term adjustments for USPTO delays, terminal disclaimers, continuation applications, and maintenance fees-and you’ve got one of the most complex systems in the world. The USPTO’s own manual (MPEP Section 2700) is over 100 pages long just on patent term calculation.

If you’re managing patents internationally, don’t rely on assumptions. Every country has its own rhythm. What’s true in Germany isn’t true in Vietnam. What’s true in 2025 isn’t true for a patent filed in 2010. The only way to get it right is to track each patent individually-with the right data, the right tools, and the right understanding of local rules.

olive ashley

December 6, 2025 AT 10:39Of course the US and EU get extra time for drug patents-because billionaires need to keep pricing life-saving meds at $500k a dose. Meanwhile, India’s just trying to keep people alive. This isn’t patent law-it’s corporate feudalism dressed up as innovation. And don’t even get me started on how maintenance fees kill small inventors. They don’t want you to succeed-they want you to fail quietly so they can buy your idea for $5k later.

Priya Ranjan

December 8, 2025 AT 10:23India doesn't give extensions because we don't need to play your broken game. You spend 15 years patenting a pill and then charge a fortune? We make generics. That’s not theft-that’s justice. Your ‘20-year term’ is a scam designed to keep the Global North rich and the rest of us medicated but poor. Your system is designed to fail us-and it’s working.

Gwyneth Agnes

December 9, 2025 AT 07:35Maintenance fees kill patents. Period.

Ashish Vazirani

December 10, 2025 AT 08:14Why are you even talking about Brazil’s backlog? They can’t even count their own population properly! And now you want us to believe their patent office is slower than their traffic? Ha! In India, we wait 12 years for a passport-but we still get our generics on time. Your ‘patent system’ is just a way for Western pharma to pretend they’re inventing while we’re actually saving lives. Don’t flatter yourselves.

Dan Cole

December 11, 2025 AT 04:45Let’s not confuse legal architecture with moral legitimacy. The 20-year term is a social contract-meant to incentivize innovation, not entrench monopolies. But when you layer on PTEs, SPCs, provisional filings, terminal disclaimers, and maintenance fee traps, you’re no longer incentivizing innovation-you’re constructing a legal labyrinth that only corporations with legal teams of 50 can navigate. The patent system was never meant to be a financial instrument. It was meant to be a bargain: disclose your invention, and for a limited time, you get exclusivity. Now? It’s a hedge fund with paperwork.

Max Manoles

December 12, 2025 AT 11:51I’ve worked in IP for 15 years and this is the most accurate breakdown I’ve seen. The real issue isn’t the law-it’s the lack of awareness. Most startups think filing a PCT means they’re protected everywhere. Nope. They’re just delaying the inevitable bill. I’ve seen companies lose $2M+ because they missed a German annuity payment. It’s not glamorous, but tracking maintenance fees across 30 jurisdictions with different due dates? That’s the real work. Use software. Don’t use Excel. Please.

Katie O'Connell

December 13, 2025 AT 14:14One must observe, with considerable consternation, the profound dissonance between the theoretical elegance of the TRIPS Agreement and the grotesque operational inefficiencies of its implementation. The notion that a patent’s expiration may be functionally nullified by bureaucratic inertia in jurisdictions such as Brazil, or by financial precarity among individual inventors, reveals not merely a flaw in procedure-but a systemic failure of epistemic equity. One is compelled to ask: Is intellectual property, in its current form, an instrument of progress-or merely a mechanism of exclusion?

Akash Takyar

December 14, 2025 AT 11:50Good insights, everyone. I want to add-utility models are underused gems. In India, we’ve seen small manufacturers use them successfully for tools and household gadgets. They’re cheaper, faster, and perfect for products that turn over in 3-5 years. Don’t over-patent. Patent smart. And yes, track your fees. I’ve helped 3 small businesses avoid losing patents just by setting calendar alerts. It’s not glamorous-but it works.

Karen Mitchell

December 14, 2025 AT 19:17So you’re telling me that the entire global patent system is just a series of loopholes and delays designed to benefit corporations? Shocking. I’m sure the inventors who spent 10 years developing this stuff didn’t expect to be outmaneuvered by bureaucratic incompetence and corporate greed. But hey, at least the EU made it easier to pay 17 different fees at once. Progress.

Myles White

December 15, 2025 AT 10:31Look, I’ve managed patent portfolios for Fortune 500s and startups alike, and honestly? The real tragedy isn’t the expiration dates-it’s the myth that patents are about innovation. They’re not. They’re about control. The reason big pharma files 50 patents on one drug? Not because they invented 50 things-they invented one thing and then patented the color of the pill, the shape of the capsule, the time of day you take it, the flavor, the packaging, the damn barcode. The 20-year term? It’s a smokescreen. The real game is stacking patents so no one can legally copy anything without violating ten different claims. And then they cry when generics come in. It’s not a system-it’s a siege engine.