Pharmacokinetic Studies: The Real Standard for Proving Generic Drug Equivalence

When you pick up a generic pill at the pharmacy, you expect it to work just like the brand-name version. But how do regulators know it’s truly the same? The answer lies in pharmacokinetic studies-the most widely used method to prove that a generic drug behaves the same way in the body as its branded counterpart. Yet calling it the "gold standard" is misleading. It’s not perfect. It’s not always enough. And for some drugs, it’s not even the best option.

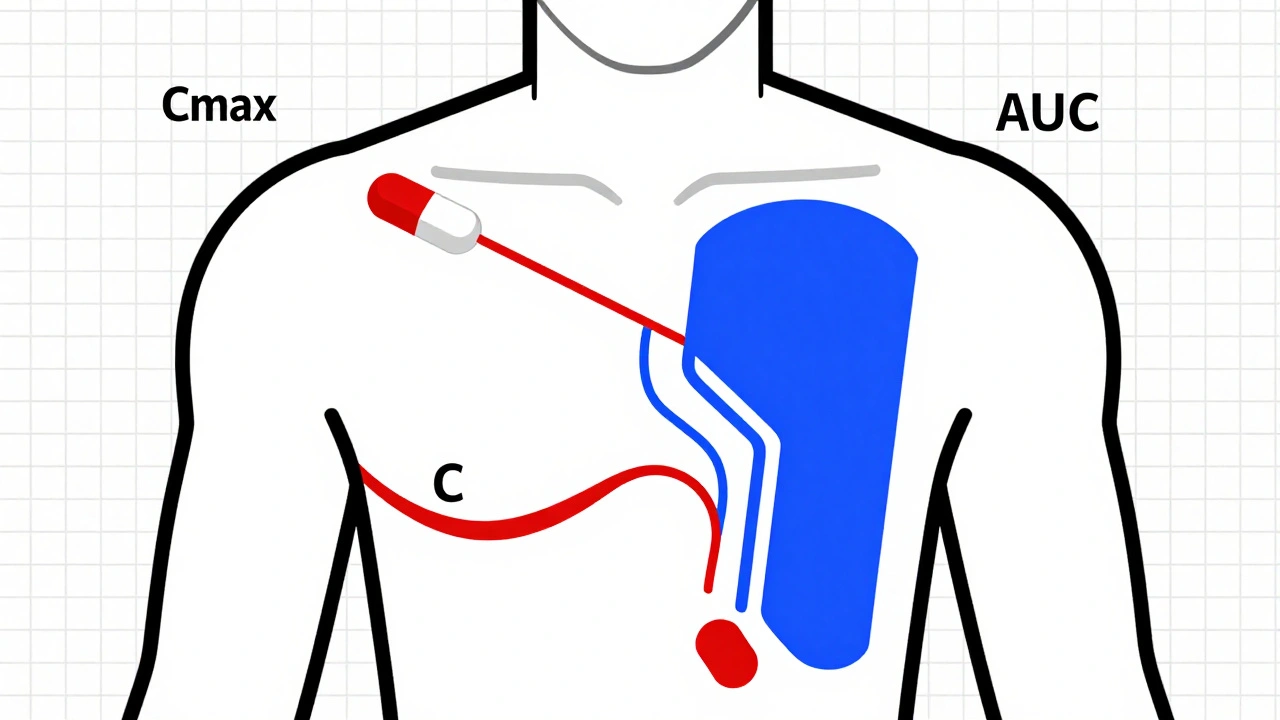

What Pharmacokinetic Studies Actually Measure

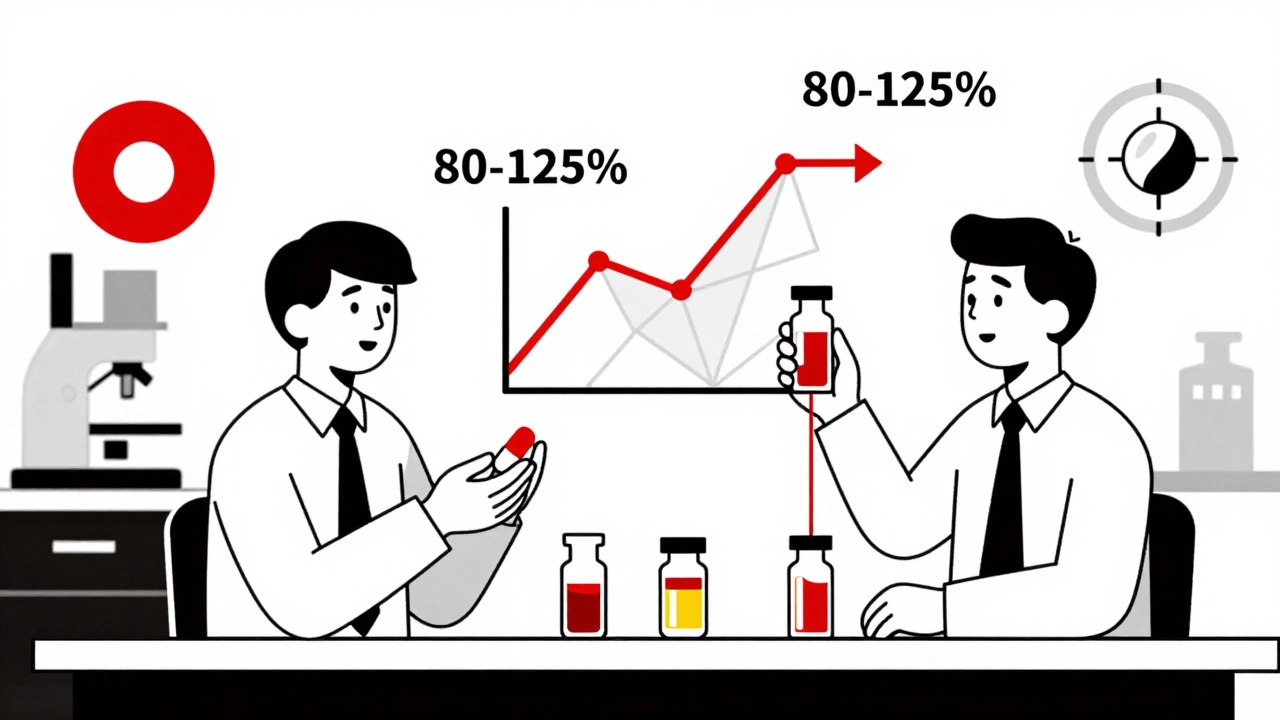

Pharmacokinetic studies track how your body handles a drug after it’s taken. Specifically, they measure two key things: how fast the drug gets into your bloodstream (Cmax, or maximum concentration) and how much of it gets absorbed over time (AUC, or area under the curve). These numbers tell regulators whether the generic version delivers the same amount of medicine at the same speed as the original.The rules are strict. For most oral drugs, the 90% confidence interval for the ratio of the generic to the brand-name drug must fall between 80% and 125%. That means if the brand drug gives you an AUC of 100 units, the generic must deliver between 80 and 125 units. If it’s outside that range, it’s not approved.

These studies are done in healthy volunteers-usually 24 to 36 people-using a crossover design. Each person takes both the brand and generic versions at different times, with a washout period in between. They’re tested under fasting conditions and sometimes after eating, because food can change how well a drug is absorbed. The data is analyzed using statistical methods like ANOVA to make sure any differences are within acceptable limits.

Why It’s Not Actually a "Gold Standard"

The FDA doesn’t call pharmacokinetic studies the "gold standard." They call them a "fundamental principle." That’s not just semantics. It’s a crucial distinction.Therapeutic equivalence means the generic drug must work the same way in real patients-not just show similar blood levels. For most drugs, blood levels are a reliable proxy. But for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index (NTI)-like warfarin, phenytoin, or digoxin-tiny differences in absorption can lead to serious side effects or treatment failure. For these, regulators often tighten the range to 90-111% and require additional testing.

And here’s the problem: even when blood levels look identical, the drugs might not work the same. A 2010 PLOS ONE study found that two generic versions of gentamicin, both meeting all pharmacokinetic criteria and labeled as pharmaceutical equivalents, still showed different clinical effects. The active ingredient was the same. The dissolution profile was the same. But patients responded differently. That’s because pharmacokinetic studies don’t measure what the drug actually does in the body-they only measure how much gets into the blood.

Where Pharmacokinetic Studies Fall Short

For simple, immediate-release oral pills, pharmacokinetic studies work well. The failure rate is under 2%, according to FDA data. But for complex products, they’re often inadequate.Take topical creams, gels, or inhalers. You can’t easily measure drug levels in the skin or lungs the same way you measure them in blood. A study in Frontiers in Pharmacology (2024) found that clinical endpoint trials for topical products would need over 500 patients to detect meaningful differences-impractical and expensive. So regulators now rely on alternatives like in vitro permeation testing (IVPT), which uses human skin samples to see how much drug passes through. One study showed IVPT was more accurate and less variable than clinical trials for semisolid drugs.

Modified-release tablets are another challenge. A small change in an inactive ingredient-like a coating or filler-can alter how slowly the drug releases. Two versions might have identical Cmax and AUC, but one releases the drug in bursts while the other gives steady levels. That’s dangerous for drugs like extended-release opioids or hypertension medications. Pharmacokinetic studies might miss this entirely.

The Cost and Complexity Behind the Scenes

Running a single bioequivalence study isn’t cheap. It costs between $300,000 and $1 million-and takes 12 to 18 months from start to finish. That’s why many generic manufacturers start with the Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS). If a drug is highly soluble and highly permeable (BCS Class I), regulators may waive the human study altogether. But only about 15% of drugs qualify.There are over 1,857 product-specific guidances from the FDA as of 2023. Each one outlines exactly how to test a particular drug. There’s no one-size-fits-all rule. A generic version of metformin follows different rules than a generic version of levothyroxine. Manufacturers must navigate this maze carefully. One wrong assumption, one overlooked excipient, and the entire study fails.

What’s Changing in the Field

The field is evolving. The FDA’s Complex Generic Drug Products Initiative, launched in 2018, now includes 149 product-specific guidances for tricky drugs like inhalers, patches, and injectables. And a new tool is gaining traction: physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling.PBPK uses computer simulations to predict how a drug behaves in the body based on its chemical properties, the formulation, and human physiology. Since 2020, the FDA has accepted PBPK models to support bioequivalence waivers for certain BCS Class I drugs. This reduces the need for human studies, speeds up approvals, and cuts costs.

For topical drugs, dermatopharmacokinetic methods (DMD) are showing promise. A 2019 study found DMD could detect differences in bioavailability with over 90% accuracy-far better than traditional clinical trials. This could replace invasive, expensive studies for creams and ointments.

Global Differences and Regulatory Chaos

The rules aren’t the same everywhere. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) takes a more rigid approach than the FDA. It applies the same 80-125% range to almost all drugs, regardless of complexity. The FDA, by contrast, tailors its requirements per product. That creates headaches for global manufacturers trying to get approval in both regions.Meanwhile, the World Health Organization (WHO) has helped 50 national regulators align with international standards. But implementation varies. In some countries, studies are poorly designed. In others, labs lack proper equipment. The result? A generic drug approved in one country might not meet the same standard in another.

What This Means for Patients

For most people, generic drugs are safe and effective. The system works well for the vast majority of medications. But patients on NTI drugs should be aware: switching generics isn’t always risk-free. Some doctors recommend sticking with the same manufacturer for drugs like levothyroxine or warfarin-not because generics are bad, but because small formulation differences can add up over time.And if you’ve ever noticed a change in how a generic drug works after a switch, you’re not imagining it. There’s documented evidence that even FDA-approved generics can behave differently in real life. That’s why regulators are moving toward more sophisticated tools-not to replace pharmacokinetic studies, but to complement them.

The Future of Bioequivalence

Pharmacokinetic studies aren’t going away. They’re still the backbone of generic approval for most drugs. But the future belongs to a smarter, more flexible system. One that uses PBPK modeling for simple drugs, IVPT for topical products, and clinical endpoint studies only when absolutely necessary.The goal isn’t to prove two drugs have identical blood levels. It’s to prove they have identical effects in patients. And that’s a higher bar than any single test can meet.

Are generic drugs always as effective as brand-name drugs?

For most drugs, yes. The FDA approves over 95% of generics based on pharmacokinetic studies, and post-marketing data shows they work just as well. But for narrow therapeutic index drugs-like warfarin, levothyroxine, or phenytoin-small differences in absorption can matter. Some patients and doctors prefer to stick with one manufacturer to avoid potential variability.

Why do some people say generic drugs don’t work as well?

Sometimes, it’s because the generic has a different inactive ingredient that affects how the drug is released or absorbed. For example, a change in the coating of a time-release pill can alter its release profile, even if the active ingredient is identical. Pharmacokinetic studies might not catch this if the Cmax and AUC still fall within the 80-125% range. Real-world effects can differ, especially in sensitive patients.

What’s the difference between pharmaceutical and therapeutic equivalence?

Pharmaceutical equivalence means two drugs have the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration. Therapeutic equivalence means they work the same way in the body-same effect, same safety. A drug can be pharmaceutically equivalent but not therapeutically equivalent. That’s why bioequivalence studies are needed: to prove therapeutic equivalence.

Can in vitro tests replace human pharmacokinetic studies?

For some drugs, yes. For highly soluble and permeable drugs (BCS Class I), in vitro dissolution tests can be enough to waive human studies. For topical products, in vitro permeation testing (IVPT) using human skin is now accepted by regulators as a reliable alternative. Research shows IVPT can be more accurate and less variable than clinical trials for creams and gels.

Why are bioequivalence studies so expensive?

They require controlled clinical settings, trained staff, specialized lab equipment, and a group of healthy volunteers who must be monitored closely over days. Each participant receives multiple doses under strict conditions, and blood samples are collected frequently. The entire process takes 12-18 months and costs between $300,000 and $1 million per study. For complex drugs, multiple studies may be needed under different conditions (fasting, fed, etc.), driving costs even higher.

Do all countries use the same bioequivalence standards?

No. The U.S. FDA and EMA have different approaches. The FDA uses product-specific guidelines, adjusting limits based on the drug. The EMA uses a more uniform 80-125% range for almost everything. WHO guidelines are followed by about 50 countries, but enforcement varies. Some emerging markets lack the infrastructure to conduct high-quality studies, leading to potential inconsistencies in generic quality worldwide.

nithin Kuntumadugu

December 12, 2025 AT 18:27John Fred

December 13, 2025 AT 19:45Lauren Scrima

December 13, 2025 AT 21:15sharon soila

December 14, 2025 AT 16:52nina nakamura

December 15, 2025 AT 19:50Hamza Laassili

December 16, 2025 AT 15:00Constantine Vigderman

December 18, 2025 AT 07:08Cole Newman

December 19, 2025 AT 04:09