Preterm Infants and Medication Side Effects: What NICU Teams Need to Know

NICU Medication Dosing Calculator

Why This Matters

Preterm infants process medications differently than full-term babies. Their liver and kidney function are immature, requiring dose adjustments based on gestational age rather than just birth weight.

When a baby is born too soon, every decision matters-especially when it comes to medication. Preterm infants, born before 37 weeks, don’t just need extra care-they need completely different medicine. Their bodies aren’t ready to process drugs like older babies or adults. What works for a full-term newborn can be dangerous or even deadly for a baby born at 24 weeks. Yet, nearly every preterm infant in the NICU gets at least one medication during their stay. And many get several. The problem isn’t that doctors are overmedicating. It’s that we’re still using tools designed for adults on tiny, developing bodies that don’t respond the same way.

Why Preterm Infants Are So Sensitive to Medications

| System | Immaturity at 28 Weeks | When It Reaches Adult Function |

|---|---|---|

| Liver Metabolism (CYP450) | 30% of adult activity | 12 months postnatal |

| Kidney Clearance | 20-40% of adult function | 6-12 months |

| Protein Binding | Low albumin levels | 3-6 months |

| Body Fat/Water Ratio | High water, low fat | Varies by drug |

Imagine giving a child’s medicine to a newborn. That’s what happens when we use adult dosing rules for preterm babies. Their livers can’t break down drugs efficiently. Their kidneys can’t flush them out. Their blood doesn’t hold onto medications the same way. Even something as simple as fluid balance changes how drugs spread through their bodies. A baby with a patent ductus arteriosus (PDA)-a common heart issue in preemies-can have up to 80% more volume for drugs to spread into. That means a standard dose could become dangerously high.

And here’s the kicker: we don’t even know how most of these drugs behave in preemies. Only 35% of medications used in NICUs have official approval for use in infants. The rest? Prescribed off-label. That includes 92% of respiratory drugs. We’re giving these babies medicine without clear safety data because we have no better option. But that doesn’t make it safe.

The Hidden Risks of Common NICU Drugs

Some medications are unavoidable. But that doesn’t mean they’re harmless. Caffeine citrate, for example, is the go-to treatment for apnea of prematurity. It works. But 18.7% of babies on standard doses develop fast heart rates. Nearly 1 in 10 have trouble feeding. Dose adjustments aren’t optional-they’re necessary. Yet, many NICUs still use fixed dosing based on birth weight alone, ignoring how the baby’s condition changes day by day.

Then there’s morphine and fentanyl. Used for pain during procedures or mechanical ventilation, these opioids are powerful. But they linger in preterm babies. Their bodies can’t clear them quickly. That leads to longer sedation, breathing problems, and even long-term brain changes. Studies show that 42.7% of extremely preterm infants get opioids during their NICU stay. And we now know that early, repeated opioid exposure may affect how neural pathways form.

Benzodiazepines like midazolam are another concern. Used for sedation, they’re given to over a quarter of preterm infants. But they’re linked to worse neurodevelopmental outcomes. The American Academy of Pediatrics now advises against routine use-not because they don’t work, but because the risks outweigh the benefits in many cases.

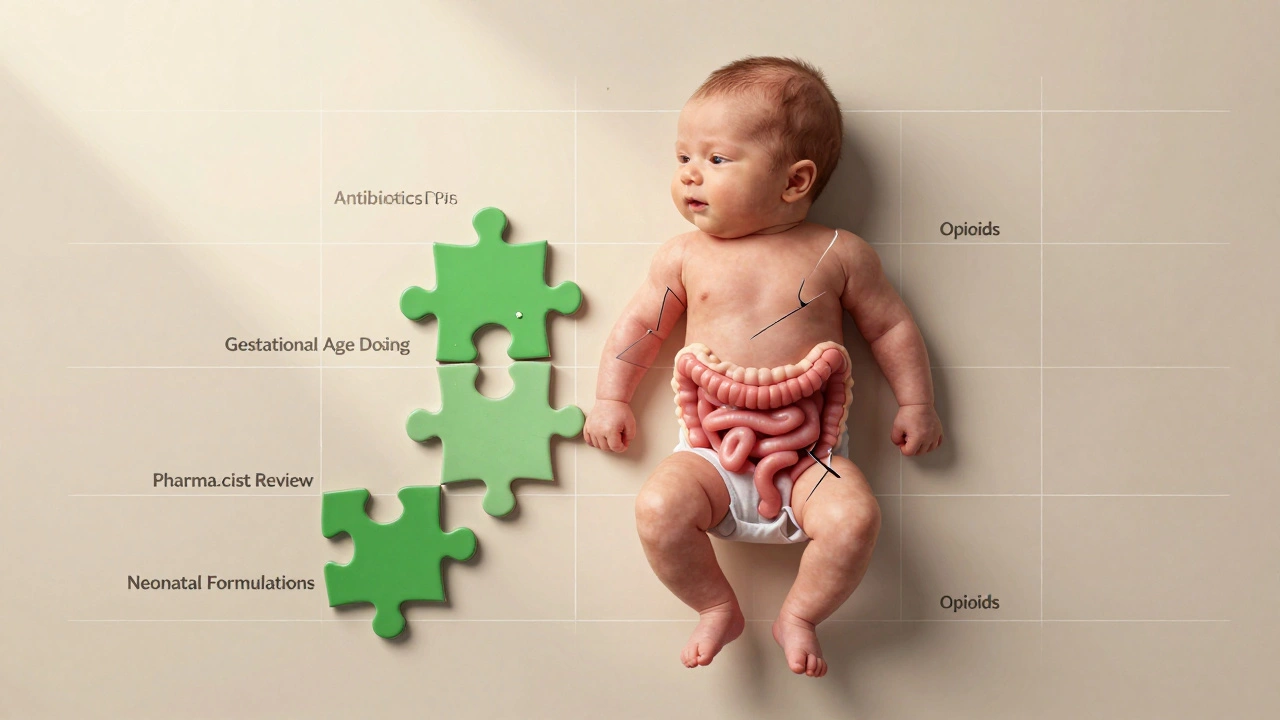

Antibiotics are perhaps the most troubling. Preterm infants are often started on antibiotics “just in case” they have an infection. But in nearly half of those cases, no infection is ever confirmed. And the damage isn’t just short-term. One study found that preterm babies exposed to antibiotics had 47% more harmful bacteria in their gut, 32% fewer good bacteria, and nearly three times more antibiotic-resistant genes. These changes don’t disappear after discharge. They stick around for years. One parent shared on a support forum that their son, now two, had five ear infections and two rounds of antibiotics after a 28-day course in the NICU-despite no confirmed infection. That’s not rare.

Anti-Reflux Medications: A Widespread Mistake

It’s common to see a preterm baby on acid-suppressing drugs like proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) or H2 blockers. Parents and staff assume reflux is causing fussiness or feeding problems. But here’s the truth: there’s no solid evidence these drugs help preterm infants. A 2022 Cochrane review found no benefit. Yet, 41% of NICU graduates still get them. Why? Because it’s easier than adjusting feeding positions, pacing feeds, or waiting for the baby’s digestive system to mature.

The cost? Much higher than we thought. Preterm infants on these drugs have a 1.67 times higher risk of necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC)-a life-threatening gut disease. They’re 1.89 times more likely to get late-onset sepsis. And their risk of bone fractures doubles. These aren’t minor side effects. These are serious, preventable harms. In January 2024, the AAP updated its guidelines to explicitly recommend against routine use of anti-reflux meds in preterm infants. It’s a long-overdue change.

Neuroprotection: Magnesium Sulfate’s Double-Edged Sword

Magnesium sulfate given to mothers before preterm birth is one of the few interventions proven to reduce cerebral palsy. The BEAM trial showed a 30% drop in risk for babies born before 28 weeks. That’s huge. But it’s not risk-free. In infants under 26 weeks, exposure to antenatal magnesium sulfate increased the risk of meconium-related ileus by 2.4 times. That’s a rare but serious bowel blockage. The benefit is clear. But the trade-off is real. It’s not about avoiding the drug-it’s about knowing who it helps and who it might hurt.

How NICUs Are Getting Better

Change is happening, but slowly. Some NICUs now use pharmacokinetic modeling software like DoseMeRx. These tools adjust doses based on gestational age, weight, organ function, and even the baby’s current illness. One study showed a 58.7% drop in dosing errors for babies under 28 weeks. That’s life-saving.

Standardized weaning protocols for opioids and sedatives are also making a difference. NICUs that implemented them cut medication exposure by nearly two weeks-without increasing pain or distress. That’s proof that less can be better.

Pharmacists are now playing a bigger role. In 76.3% of NICUs, medication protocols are adjusted based on gestational age. For drugs like fentanyl, the difference between a 24-week and a 32-week infant can mean a 40% dosing change. Without a pharmacist reviewing every dose, errors happen. And they happen often: 68.4% of NICU nurses report at least one medication error per month, and nearly a quarter of those lead to harm.

What Needs to Change

We need more than better dosing. We need better drugs. Only 12 of the 50 most commonly used NICU medications have official neonatal dosing guidelines. The rest? Guesswork. The FDA’s Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act has helped, adding 15 new pediatric labels since 2002. But progress is too slow.

That’s why the Neonatal Precision Medicine Initiative launched in 2023. It aims to build personalized dosing models for 25 high-risk medications by 2026. And there’s hope on the horizon: a new fentanyl formulation designed just for preterm babies (NeoFen) is in FDA Fast Track review, with approval expected in early 2025.

But the biggest change isn’t technological. It’s cultural. We need to stop assuming that if a drug works in adults or older babies, it’s safe for preterms. We need to stop giving antibiotics “just in case.” We need to stop using acid blockers for reflux that doesn’t need treatment. We need to stop treating preterm infants like small adults.

Every medication given in the NICU is a gamble. The goal isn’t to avoid all drugs. It’s to use the right one, at the right dose, for the right reason-and only when necessary.

What Parents Should Ask

If your baby is in the NICU, you have the right to ask:

- Why is this medication being given?

- Is there evidence it helps preterm infants like mine?

- Are there alternatives that don’t carry the same risks?

- How will we know if it’s working-or causing harm?

- What’s the plan to stop it if it’s not needed?

Don’t be afraid to push for answers. You’re not overstepping-you’re protecting your child.

parth pandya

December 2, 2025 AT 21:36Man, I read this whole thing and my brain hurt in the best way. I work in a NICU in Delhi and we're still using adult dosing charts for some meds because the pediatric guidelines aren't printed anywhere. I saw a 26-weeker get a full adult dose of ampicillin once. Thank god the pharmacist caught it. We need better training, not just better drugs.

Charles Moore

December 4, 2025 AT 07:45This is one of those posts that makes you realize how much we're guessing with these tiny humans. I'm a neonatal nurse in Ireland and I've seen parents get tearful because they're told their baby 'needs' an acid reducer when the baby's just gassy. We've started teaching parents to hold their babies upright after feeds instead. It's not glamorous, but it works. And it doesn't turn their gut into a chemical warzone.

Gavin Boyne

December 4, 2025 AT 08:23So let me get this straight-we're giving preemies opioids because they're 'in pain' from being poked with needles, but we don't have a clue how those opioids are rewiring their brains? And we call this medicine? Wow. I mean, I get it. We're scared. We want to fix everything. But when your solution is basically drugging a newborn into silence, maybe the problem isn't the baby. Maybe it's the system. Also, who approved 'just in case' antibiotics as a medical philosophy? That's not a treatment. That's a prayer.

sagar bhute

December 5, 2025 AT 23:20This is why Indian hospitals shouldn't be allowed to run NICUs. You people don't even know how to dose a baby. Look at the stats-47% more bad bacteria? That's not science, that's negligence. You're killing these kids with your ignorance. And now you want to blame the FDA? Pathetic. We need Indian doctors to stop copying American protocols and start thinking. This is a third-world disaster wrapped in a white coat.

shalini vaishnav

December 6, 2025 AT 09:59Of course Western medicine is failing preterm infants-because they're too busy trying to 'personalize' everything instead of going back to basics. In India, we used to just feed them warm milk, keep them warm, and let nature take its course. No drugs. No machines. No 'pharmacokinetic modeling.' You think your fancy software is helping? It's just making you feel important while the baby still cries. This isn't progress. It's arrogance dressed in data.

Gene Linetsky

December 8, 2025 AT 04:07Wait-so you're telling me the FDA approved a drug for adults, then we just give it to babies without testing it? And you're surprised they have brain damage? That's not an accident. That's a cover-up. The pharmaceutical companies are pushing these drugs because they're profitable. The NICU is a testing ground. They don't care if the baby lives or dies-just that the paperwork says 'approved.' I've seen the emails. They're not hiding it. They're bragging about it. And now you want to talk about 'guidelines'? LOL. Wake up.

Ignacio Pacheco

December 9, 2025 AT 22:35Interesting that you mention NeoFen. I read the phase 2 trial data last month. The half-life in 24-weekers was 3.2x longer than in adults. That’s not a tweak-that’s a whole new pharmacology. But here’s the thing: if we’re going to design drugs for preemies, why not design the entire NICU around them? Like, what if we stopped treating them like broken adults and started treating them like… babies? Who knew?

Jim Schultz

December 11, 2025 AT 17:53STOP GIVING ANTIBIOTICS JUST IN CASE!!!!!!!!! This is not a game!!!!!!!!! We are not playing Russian roulette with newborns!!!!!!!!! The gut microbiome is not a suggestion-it's the foundation of their entire immune system!!!!!!!!! And you're wiping it out with a 7-day course of ampicillin because you're too lazy to wait 48 hours for cultures????????? I've seen babies die from C. diff at 3 weeks old because of this!!!!!

Kidar Saleh

December 12, 2025 AT 19:45I’ve worked in NICUs from London to Lagos, and the one thing I’ve learned is this: the best medicine is often the one you don’t give. I had a 25-weeker who was on morphine for 17 days. We weaned him off using only skin-to-skin, swaddling, and quiet. He cried less. Slept better. Gained weight. No side effects. No withdrawal. Just human touch. Sometimes, the most advanced tool we have… is our hands.