When Do Drug Patents Expire? Understanding the 20-Year Term and Real-World Timeline

Most people think a drug patent lasts 20 years. That’s what you hear on TV, in news headlines, even from your pharmacist. But if you’re waiting for a cheaper version of your medication to show up after exactly 20 years, you’ll be disappointed. The real story is far more complicated - and it’s why your prescription still costs hundreds of dollars even when the drug is decades old.

What the 20-Year Patent Really Means

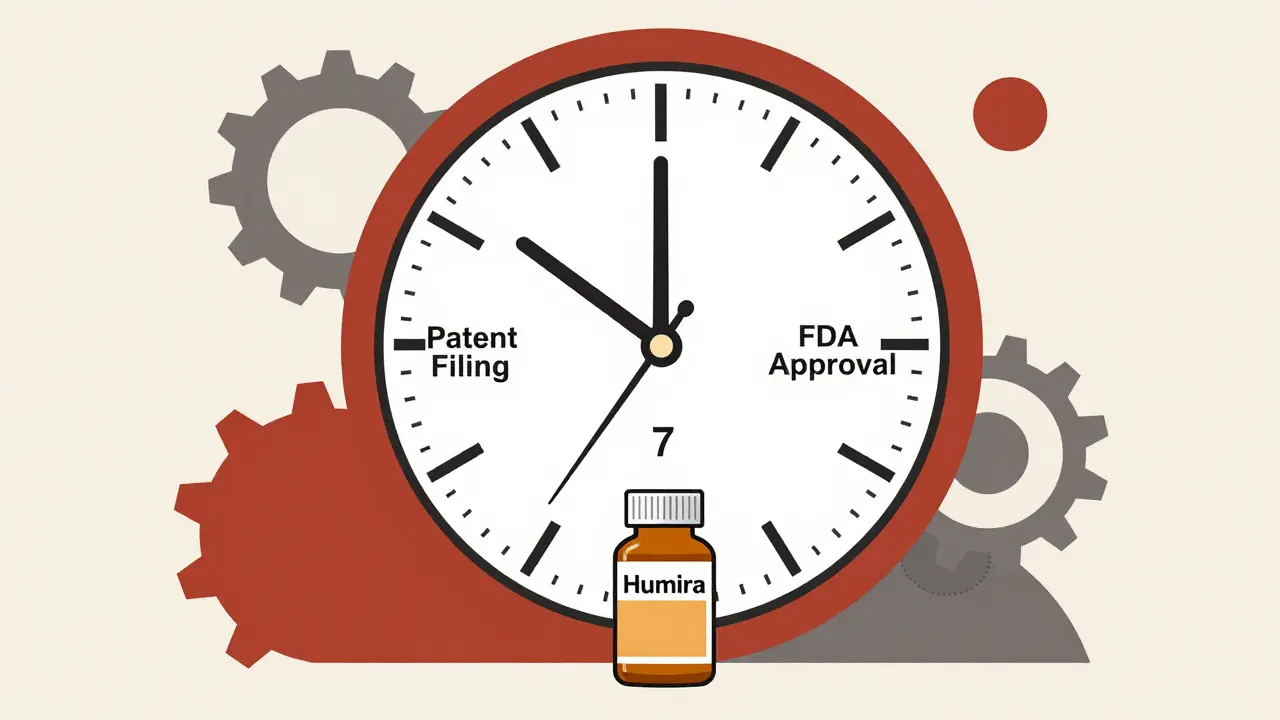

The 20-year clock starts ticking the day the patent application is filed - not when the drug hits the market. That’s crucial. Most drugs take 10 to 12 years just to get from lab to pharmacy. Clinical trials, safety reviews, FDA approvals - it all eats up time. By the time a drug like Humira or Eliquis is approved, only 7 to 10 years of patent life are left. That’s not a loophole. It’s the system working as designed.

The U.S. patent system changed in 1995 to match global standards. Before that, patents lasted 17 years from the date they were granted. But that created a problem: companies could delay filing patents until right before approval, stretching exclusivity way beyond what was fair. The 20-year rule from filing fixed that. Now, the clock starts when the inventor first submits the paperwork, no matter how long it takes to get approval.

Why Your Drug Still Hasn’t Gone Generic

Just because a patent expires doesn’t mean generics show up overnight. There are layers of protection built into the system - and pharmaceutical companies use them all.

The Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 is the backbone of this system. It lets drugmakers apply for a patent extension - up to five extra years - to make up for time lost during FDA review. But there’s a catch: the total time a drug has market exclusivity can’t go beyond 14 years after FDA approval. So if a drug gets approved in 2018, the latest it can stay protected is 2032, even if the original patent was filed in 2005.

That’s not the only tool. There’s also:

- Regulatory exclusivity: New chemical entities get 5 years of FDA data protection. No generic can even file an application during that time.

- Orphan drug exclusivity: For rare diseases, you get 7 years - no exceptions.

- Pediatric exclusivity: If a company runs extra studies on kids, they get 6 months added to any existing patent or exclusivity period.

- Method-of-use patents: A drug might be patented for treating diabetes, but if a company finds it works for weight loss too, they file a new patent on that use. That’s a whole new 20-year clock.

Take Spinraza, a drug for spinal muscular atrophy. Its main patent filed in 2013 expires in 2033 - not because the original compound is new, but because of a portfolio of 12 different patents covering delivery methods, dosing schedules, and formulations. Each one has its own 20-year term. Together, they create a wall.

The Patent Cliff: What Happens When the Exclusivity Ends

When a major drug loses patent protection, it’s called the “patent cliff.” It’s not just a buzzword - it’s a financial earthquake. In 2020, Humira lost its last key patent. That single drug brought in $21 billion in sales the year before. Within 18 months, biosimilars captured over 70% of the U.S. market. Prices dropped by more than 60%.

It’s the same story with Eliquis. After its patent expired in December 2022, generic versions hit the market. Six months later, they held 35% of sales. By the end of the first year, the average wholesale price dropped 62%. Patients paid less. Insurers paid less. But the original maker lost billions.

That’s why companies fight to delay the cliff. They file dozens of secondary patents - for packaging, for pill coatings, for minor chemical tweaks. The FTC found these tactics can delay generics by 2 to 3 years on average. One 2023 study showed 78% of drugs facing patent expiration use at least one lifecycle strategy like this.

How Long Until Your Drug Gets Cheaper?

There’s no single answer. It depends on:

- What kind of drug it is: Small molecule drugs (like statins or blood pressure meds) usually go generic fast. Biologics (like insulin or cancer drugs) take longer - often 10+ years - because biosimilars are harder and costlier to make.

- Who challenges the patent: The first generic company to file a “Paragraph IV” certification (claiming the patent is invalid or won’t be infringed) gets 180 days of exclusive rights to sell their version. That’s a huge incentive. But if no one challenges it, the patent stays unchallenged - and generics don’t enter.

- Whether lawsuits are filed: If the brand-name company sues the generic maker within 45 days of the application, the FDA must wait 30 months before approving the generic - unless the court rules sooner. Many lawsuits drag on for years.

For example, a drug like metformin, with no strong patent protection and no lawsuits, went generic within a year. But a drug like Myrbetriq, with multiple patents and aggressive litigation, didn’t see generics until 12 years after approval - even though the original patent technically expired after 10.

What’s Changing in 2025 and Beyond

The system is under pressure. In 2024, Congress introduced a bill called the Restoring the America Invents Act, which would cut back on patent term adjustments. If passed, it could shorten market exclusivity by 6 to 9 months on average.

The USPTO is also rolling out new software to automate patent term calculations. That means fewer errors, fewer delays - but also less room for companies to game the system.

Meanwhile, global trends are shifting. The World Health Organization is pushing for a 15-year patent term worldwide to improve access to medicines. The U.S. pharmaceutical industry, led by PhRMA, argues that the current 20-year system is necessary to recoup the $2.3 billion average cost of developing a new drug.

But here’s the reality: the average drug doesn’t even make back its R&D costs until 8 to 10 years after launch. The rest of the patent life? That’s pure profit.

How to Find Out When Your Drug Expires

If you’re curious when your medication might get cheaper, check the FDA’s Orange Book. It’s the official list of approved drugs and their patents. Every innovator company must list their patents within 30 days of approval. Over 98% do.

You can search by drug name, active ingredient, or company. The Orange Book shows:

- The patent number

- The expiration date

- Whether it’s a product, method, or use patent

- Any patent term extensions granted

It’s not perfect - some patents are listed late, or the dates are wrong - but it’s the best public source you’ve got.

Pharmacists and patient advocacy groups also track patent expirations. Sites like DrugPatentWatch and Generics Intelligence offer free tools to monitor upcoming expirations. You don’t need to be a lawyer to use them.

What This Means for Patients

When your drug’s patent expires, it doesn’t mean instant savings. Sometimes, your insurance switches you to a generic - but not always. In 2023, one patient wrote to the FDA complaining that their insurer switched them from a $50 copay on brand-name drug to a $200 copay on a generic - because the brand had a 6-month pediatric exclusivity extension, and the generic wasn’t covered yet.

That’s the paradox: the system is meant to protect innovation, but patients often pay the price during the transition. The longer the exclusivity, the longer you pay full price.

But there’s hope. As more patents expire - especially in 2025, when over $62 billion in drug sales are projected to fall off the cliff - prices will drop. Generics will flood the market. Biosimilars will get better. And eventually, your medication will become affordable.

It’s not about waiting 20 years. It’s about understanding how the clock really works - and when to expect change.

Do all drug patents expire after exactly 20 years?

No. The 20-year term starts from the patent filing date, but most drugs lose exclusivity much sooner due to the time needed for clinical trials and FDA approval. Some patents are extended by up to 5 years under the Hatch-Waxman Act, and others are layered with additional protections like regulatory exclusivity or pediatric extensions. The actual market exclusivity period is usually between 7 and 14 years.

Can a drug stay protected longer than 20 years?

Yes. While the original patent expires after 20 years from filing, companies often file multiple patents covering different aspects of the drug - like new formulations, delivery methods, or uses. These secondary patents can extend protection beyond 20 years. For example, a drug’s primary patent might expire in 2028, but a patent on its inhaler design could last until 2035. Regulatory exclusivity periods (like 5 years for new chemical entities or 7 years for orphan drugs) also delay generic entry independently of patents.

What is the Hatch-Waxman Act and how does it affect patent expiration?

The Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 balances innovation and access. It lets drugmakers apply for a patent term extension (up to 5 years) to make up for time lost during FDA review. It also created a fast-track pathway for generics to enter the market after patent expiration. However, the total market exclusivity can’t exceed 14 years from FDA approval. This act is why many drugs have patent extensions - and why generics can’t always launch immediately after the original patent expires.

Why do some generic drugs cost more than the brand name right after patent expiration?

That’s usually because the brand drug still has extra exclusivity - like a 6-month pediatric extension - that blocks generics from being covered by insurance. Even if the patent expired, the FDA won’t approve the generic until that exclusivity period ends. During that gap, insurers may still only cover the brand-name version, forcing patients to pay the full price. Once generics are approved and listed on formularies, prices typically drop sharply.

How can I find out when my specific drug’s patent expires?

Check the FDA’s Orange Book, which lists all patents associated with approved drugs and their expiration dates. You can search by drug name or active ingredient. The Orange Book also shows patent extensions and exclusivity periods. For more detailed analysis, tools like DrugPatentWatch or Generics Intelligence offer free public access to upcoming patent expirations and generic entry forecasts.

Do biosimilars follow the same patent rules as generics?

No. Biosimilars are complex biological drugs (like insulin or monoclonal antibodies) and face different rules. They can’t be approved until 12 years after the original biologic’s approval, regardless of patent status. Even after that, they require additional testing and FDA approval to prove similarity. As a result, biosimilars enter the market slower than small-molecule generics - often taking 10 to 15 years after the original drug’s launch.

Astha Jain

January 19, 2026 AT 14:34Aman Kumar

January 19, 2026 AT 18:57Valerie DeLoach

January 20, 2026 AT 02:32Phil Hillson

January 20, 2026 AT 14:39Lydia H.

January 21, 2026 AT 21:53Tracy Howard

January 23, 2026 AT 08:02Erwin Kodiat

January 25, 2026 AT 07:06Malikah Rajap

January 27, 2026 AT 00:05Christi Steinbeck

January 28, 2026 AT 15:26Jake Rudin

January 29, 2026 AT 11:41Jacob Hill

January 30, 2026 AT 11:26